The Detour (The Chilean Channels – Part VI)

We ended last week’s offering with the story of a fight to claw our way to windward and the subsequent casual relinquishment of all those hard won miles. So, why this detour from the ‘main drag’, winding its way from the Straits of Magellan north through the channels to Chiloe?

Whither away Mollymawk now?

Why, in the wake of our heroes, of course!

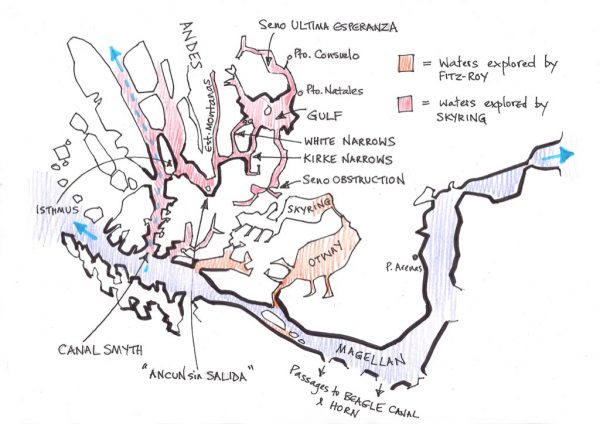

It was our old mate Bill Skyring who led us off on this latest detour, through the mountains. Skyring was intent on discovering a route which would link the canals of the Pacific coast with the Straits of Magellan, via the waters lately discovered by his colleague, Robert FitzRoy.

Pootling about in a rowing boat while the Beagle lay at anchor in Port Gallant, FitzRoy had gone all the way up the Jeronimo Channel (on the north side of the Magellan Strait, just after the bend), and at the top of that channel he had found a great lake. He named the lake in honour of Sir Robert Otway, the commander of the ‘British South American Station’ and the man who had given him this marvellous job.

Having duly crossed the Otway Water, FitzRoy found, to his astonishment, that it led into another expanse, which he christened Skyring. Had it not been for the intervention of the aforementioned Otway, William Skyring would have been skippering the Beagle, for Philip Parker King had appointed him to the post after the death of Pringle Stokes. Otway had overruled that decision – and the young usurper evidently felt the need to offer some kind of appeasement to the other chap.

Unfortunately, FitzRoy didn’t have time to explore the Skyring Water – he had to get back to the Beagle – and so it was that the task of searching for the lake from the other end fell to its namesake:

“When to the northward of Cape Tamar … or the latitude of 52° 6´, should you notice an opening to the eastward, with a current or stream of tide setting through it … you will endeavour to ascertain whether it communicates with the Skyring Water.”

[Captain Robert FitzRoy’s instructions to Lieutenant Skyring]

Again, this was not so much a command as a peace offering on FitzRoy’s part, and the captain of the Adelaide must have been pretty chuffed. If he could only find the missing link – if he could only get into the lake from the Pacific end of affairs – then he, William George Skyring, would be assured of a place in the history books. If that link existed then no one need ever again face the stormy seas in the western approaches to the Magellan Strait or off Cape Horn. The world’s merchantmen would be able to weave their way through the canals, following the route which our man by his skill and sagacity had brought to light…

Unfortunately, it didn’t quite work out like that, but there was a time when it all looked very promising.

Skyring first set out to search for the ‘link’ in a whaleboat. Leaving the Adelaide moored in the Smyth Channel, he headed south again – just as we also did (as described in the previous article), but in rather less favourable weather. It took him three days to make his way down the stretch which we covered in a couple of hours.

As he battled his way along under oars, Skyring was aware that he was following in the wake of old Sarmiento de Gamboa, that villain who condemned hundreds of men, women and children to die of hunger in Tierra del Fuego; but that came later. When he explored this stretch of the Chilean waterways, Sarmiento was still in pursuit of Drake and still searching for the entrance to the Magellan Straits. This channel which Skyring now followed, Sarmiento had labelled Ancun sin Salida – a corner with no way out.

But was he right?

Ahead of them, Skyring and his companions could see that most extraordinary confection of snow and rock which he had named for Admiral Burney. The mountain now lay to the south and west of their route.

He stopped in a bay on the western shore of the channel and, wandering inland, realised that he was only a hundred yards away from the inlet wherein the Adelaide had lain a few days earlier. Studying the chart which Burney had cooked up from Sarmiento’s account, he also realised that this isthmus lay alongside the hill where the Spanish navigator had apparently given an ‘oración‘ to his men.

Whereas not even two hundred years divided us from Skyring, he was following a trail which was more than 250 years old – and he was, as he believed, the first to follow in Sarmiento’s wake. One can sense his excitement as he takes his little open boat into this unknown territory. Surely there could be almost nothing to match the thrill of being the first to lay eyes on a new valley and a new waterway!

For us there were no such delights – but, still, we had the whole place to ourselves, and we had the satisfaction of knowing that nothing whatsoever has changed here since the ancient mariners first set eyes on this place.

After a night spent camped on the beach at a cape which he called Earnest, Skyring pushed on around Sarmiento’s ancón. Ahead of him reached a long inlet – a place which he came to know as the Channel of the Mountains. According to Sarmiento, after carving its way for miles into the mountains, the inlet came to an abrupt end.

But what about this much smaller channel on the eastward shore at the mouth of the Channel of the Mountains? Sarmiento seemed to have overlooked it. He didn’t even mention it.

Might it lead somewhere?

“They entered the smaller opening to the eastward, and were almost assured of its being a channel; for when they were between the points, many porpoises and seals were observed, and a tide was found setting westward at the rate of two knots.”

“At dark, they hauled their boat on the beach of an excellent bay, at the north side of the narrow reach, and secured her for the night.”

“On the 9th, shortly after daylight, they set out in a north-easterly direction to ascertain the truth of their supposition; and before noon [they] knew beyond a doubt, that they were correct in their belief, being in the narrows of a channel before unknown, that had eluded Sarmiento’s notice.”

What excitement they must have felt!

“A strong tide took the boat through… forming whirling eddies, which were carefully avoided by Lieutenant Skyring.”

Skyring named the narrows for his second-in-command, one James Kirke. (Was the scriptwriter for StarTrek also a fan of FitzRoy et alia, or is it a coincidence that he used this name for the captain of his spacecraft?)

Having passed safely through the eddies the whaleboat emerged into a new channel. It was upwards of two miles wide, and on their left it ran away to the north for at least eight miles before turning eastward. On their right, it trended to the south-east for two or three miles and then also turned to the eastward.

One can imagine with what feelings of delight the men gazed upon this new world. And even more exciting than the discovery of a series of channels was the fact that they had sailed right through the mountain range. Behind them lay that familiar world of snow-capped peaks whose lower slopes were cloaked in scrubby trees; and ahead were low born mountains and flat plains. The contrast is is so spectacularly different as to defy belief, and when we made this same journey I felt that we had stepped out of Narnia and stumbled into the wardrobe.

Caesar put it more prosaically but more accurately: “So, we’re back in Argentina,” he said.

It must have seemed to Skyring that his dream had come true. FitzRoy had told him that the eastern end of the Otway and Skyring Waters was surrounded by arid plains and low hills. This place fitted the description perfectly. Now all that was wanting was for him to rush into this new world and “prosecute the discovery” (his words).

Unfortunately, however, the journey had taken longer than anticipated, and the men only had one more day’s food left. The temptation to press on was great, but he must resist it; he must turn back.

“Bitterly regretting”, they retraced their steps, went back through the narrows, and spent another night in the place which Skyring named Caleta Whaleboat. (The chart shows it in a different place – but the chart is wrong.)

After that they had a hard row of some fifty miles to get back to the Adelaide. It took them three days, but they were able to eke out their provisions with mussels and cormorants. They arrived just in time to stop their companions from sending out a search party.

Adelaide resumed her journey northward – a journey which we will take up at another time. There then followed some weeks in Chiloe, refitting the schooner; and then she began her journey south again.

So confident a report had Skyring given after his last cruise that he had infected everybody else with the same certainty, and his instructions from his commander before this next cruise were explicit:

“It is expected, from the results of your last survey, that you will pass through the Skyring and Otway Waters, and enter the Strait by the Jerome Channel. The above [is] the principal object of your operations.”

[Philip Parker-King to William Skyring]

By now, one imagines, Skyring must have been a-fever with anticipation. Soon, soon… Soon he would be able to tie together the ends of the survey, taking up where he had left off eight months before.

Well, the man was in a fever, alright – but it seems that he was mostly just sick with worry. Before he could resume his exploration of the channels he must complete the survey of the dreaded Golfo de Penas. It was this desperately wet and wild place which had finally driven Pringle Stokes into insanity, and the chore of tracing their steps and revisiting old haunts must have been a melancholy one. According to his own account, Skyring became too ill to work. The task of surveying the shoals and inlets passed to James Kirke and to one Alexander Millar – until Millar further dampened everybody’s spirits by suddenly dying of appendicitis.

After completing the survey of the Golfo de Penas, the Adelaide made her way south through the channels, continuing to explore as she went. And Skyring gradually recovered from the illness which assailed him, and by the time the schooner had crossed her north-bound track he was back on form. Whatever else happened, he must be fully involved in the business of finding that passage which, he was “most sanguine”, would be found to lie between the Magellan Straits and the Pacific channels.

In fact, so sure was the captain that Straits of Skyring existed that he allowed the Adelaide to become quite low on provisions.

But there – they were only a day or two away from success and Puerto Hambre, so what did it matter?

On reaching the bend which Sarmiento had labelled Ancón sin Salida, Skyring anchored for a while in the cove at the northern end of Isla Jaime.

Then, the wind seeming to be favourable, he decided to push on around the corner.

“In the evening [we] anchored in Leeward Bay [a couple of miles further to the east], which we at first thought would afford excellent shelter, but on reaching it found we had erred exceedingly.”

There was no time to look for another place, and “so we moored, and prepared for bad weather, which, as usual, was soon experienced”.

Here they remained for the next two days, “without a possibility of moving or doing anything to make our situation more secure. We had heavy squalls during the whole time.”

…

“On the 5th we got clear of this bad and leewardly anchorage, the wind being more to the north-west; but we had still such very squally weather, with rain, that it was a work of several hours to beat to Whaleboat Bay”, that place which they had discovered on their previous visit.

Mollymawk, facing similar conditions as we made our way north from Isla Jaime, also had occasion to stop here; and reaching the place we knew the same relief that Skyring surely felt.

On the following morning, the wind being down, Skyring sent Kirke to make a thorough investigation of that ‘Channel of the Mountains’ which now lay just astern and round the corner. And Kirke duly explored the inlet from one end to the other and found no anchorages and nothing of any interest to him. It’s a very beautiful place – but these men were not on a sight-seeing tour. Glaciers left them cold, if you see what I mean.

Skyring wasn’t mad keen on the idea of taking the schooner though those rather scary ‘Kirke Narrows’, which he had found on his previous trip; and so took the other whaleboat and explored another avenue, which lay to the north.

This northerly route – now known as the Santa Maria Channel – is extremely pretty, and there are a couple of really excellent caletas along the way; but Skyring doesn’t mention the scenery, and one gathers that he was not impressed by this place.

Whereas the water sluices directly through the ‘Kirke Narrows’ at up to ten knots, in the Santa Maria Channel it takes a devious path through any of three passages. Our favourite one is about half a mile long and less than thirty yards wide and is called something like Ooshy-Sloosh, but there’s also an even narrower pass which we call The Plug-Hole. And then, after you’ve been through this bit – (and, in truth, we recommend sticking to the main channel – between Isla Huerta and Cabo Escarpado – where the current often runs at less than three knots) – you still have to wend your way amongst the islands further to the east, where the tidal rips and eddies are equally exciting.

Having passed through this “narrow intricate channel” which he named White Narrows, Skyring found that he had arrived suddenly “into a clear, open bay”.

“… Eastward, we could perceive no land; to the north-east and south-eastward lay a low flat country, and the hills in the interior were long, level ranges, similar to that near Cape Gregory [at the eastern end of the Magellan Straits]. … I fully believed that our course hereafter would be in open water, along the shores of a low country, and that we had taken leave of narrow straits, enclosed by snow-capped mountains. The only difficulty to be now overcome was, I imagined, that of getting the vessel safely through the Kirke Narrow – which, hazardous as I thought the pass, was preferable to the intricate White Narrow, through which we had just passed”.

So, back they went, and they fetched the Adelaide and brought her through the Kirke Narrows. They anchored her in a place which Skyring named Easter Bay, it being Easter Tuesday.

And then off they went in their whaleboats, intent on finding the passage through to the Skyring Water and the Straits of Magellan.

Oh, alas! Poor William Skyring. One can’t help feeling sorry for him. Nobody could have tried harder to find that fabled pass. While Kirke searched the northern edge of the lake, examining each and every inlet, he paid the same thorough care to the more promising southern and eastern shores. The chart tells the tale, scattered as it is with names such as Disappointment Bay, Hope, and Ultima Esperanza – the Last Hope.

The most promising route lay down a long and winding inlet which ultimately ended in an Obstruction.

Well… in fact, it ended in a mountain. Skyring climbed a hill and saw a sheet of water – but whether it was the Skyring Water or just a lagoon lying between the two seemed hardly relevant. He had failed in his mission. The promised passage did not exist.

“The termination of Obstruction Sound is one of the most remarkable features in the geography of this part of South America,” wrote Parker King afterwards – very kindly.

The distance from the head of Seno Obstruction to the lagoons at the head of Seno Skyring is just one and a half miles.

And the irony is that the Chilean government are now knocking a way through the Obstruction.

No, they aren’t digging a canal; but they’re building a road. The road runs all the way from Puerto Natales, along the south side of the gulf, and down the side of that long, lonely inlet whose shores Skyring traced. Eventually it will link the two places.

And for what purpose?

For the purpose of servicing the salmon farms which are being developed in both Seno Obstruction and in the Skyring and Otway Waters.

Those 19th century sailors never could see the sense in so much beauty just lying around going to waste, and I doubt if they’d be upset to hear about what’s coming to this region – but they probably would be rather surprised at the way things have developed.

I’m sure they would never have expected that a little town be founded on the shallow, windswept shore on the eastern side of the gulf….

And James Kirke would no doubt be astonished, could he return, to find a cattle ranch at the head of one creeks which he explored and a yellow yacht much the same size as the Adelaide lying at anchor there.