Where do dolphins go when it’s raining?

Ever since I first heard that it was possible to listen to dolphins and record their voices, I’ve wanted to do just that: ever since I first heard that dolphins ‘talk’, I’ve wanted to get my hands on a hydrophone.

And pretty much ever since I first understood how privileged we ‘yotties’ are, in being able to wander whither we will and see the wonders of the world, I’ve wanted to share our adventures with someone who can make use of the opportunity to further mankind’s knowledge of the seas.

Well… after nigh on thirty years of day-dreaming we’ve finally managed to stitch those two objectives together. Through the friend of a friend of a nephew of mine we met one Pina Gruden, a lady whose PhD subject is Dolphin Acoustics. And through the cooperation of Pina’s university supervisor, Mollymawk has now been equipped with a state of the art hydrophone capable of hearing the full range of cetacean vocalisations.

Pina Gruden hails from a mountain village in Slovenia, a place which was still under Communist rule when she entered the world. Notwithstanding the fact that her familiar surroundings were snowy peaks, she was just eight years old when she told her family and friends that she was going to be an expert in dolphin communication. Her first step on the road to that ambition was a degree in Biology, but she followed this up with one in Engineering. Thus equipped, she has both sides of the argument covered and can hold her own not only with ‘researchy types’ but also with the people who make the machinery.

This is Pina explaining to the world in two minutes why research into dolphin acoustics matters. Her enthusiasm is totally infectious – and there’s no hamming it up for the camera; she’s like this every moment of every day.

After gaining her laurels, Pina sailed into the world of commercial cetacean acoustics, finding employment with a company whose job it is to oversee marine activities such as drilling and seismic surveying. It having been recognised that such things can have a disastrous impact on cetaceans, messing with their echo-location systems, the law in Europe insists on the presence, aboard each such vessel, of a qualified expert. Essentially, this person’s job is to prevent commercial concerns from doing damage.

Unfortunately, as Pina soon discovered, there’s no one aboard a drilling ship so hated as the person diligently watching her hydrophone’s read-out and repeatedly crying out, “No! Stop! There are cetaceans in the area.” And so, after a couple of years of banging her head on the wall, she resigned herself to the fact that one woman, all alone, can’t save the whales… and she left such work for the less scrupulous and went back into research. It’s very much less remunerative, but it’s far more enriching in other ways.

Now – one of the most interesting things about the dolphins inhabiting the coast of Chile is that they’ve hardly ever been recorded. Indeed, a couple of them have never, ever been recorded.

And one of the reasons that they’ve never been recorded is that they don’t whistle.

Bottle-nosed dolphins and common dolphins and their various kin all communicate with one another by sending out characteristic whistles. No one has any idea what they might mean, but they ‘speak’ in recognisable whistled phrases, and the expert acoustian can see the phrases, captured by the hydrophone and displayed on the computer screen, and can say, “That’s a Delphis delphinum greeting another member of its family”; or “These are whistles emitted in the presence of fish”; or what have you.

The sound-wave energy produced by whistles is easily captured by a hydrophone – it’s even within our own audible range – but the eight species of dolphin and porpoise inhabiting the coastal waters of Chile don’t make any such sounds. Instead, they appear to communicate using only the high-frequency clicks created by a cetacean ‘seeing’ its way by echo-location.

The echo-location clicks produced by these particular dolphins are right off the scale of human hearing. They’re signals, like the ones produced by our depth-sounder, which are designed to bounce off whatever lies ahead of the instrument, returning an echo. Our depth-sounder cunningly translates the returning signal into a numerical display advising us of the depth of water which lies under the keel; and a cetacean’s brain even more cleverly converts the echo-location signals sent out from the animal’s ‘melon’ into a picture of the world ahead.

According to experiments conducted with captive bottle-nosed dolphins, the animal doesn’t just ‘see’ a vague object – its equipment is so sophisticated that it can recognise shapes, of different sizes and densities, moving at different speeds. And just as our eye-brain machinery can instantly identify the specific light patterns emitted from an object moving across the big blue as an aeroplane, two miles up, with the sun glinting on its wings, so the cetacean can instantly “see” an individual tuna amongst a shoal.

The problem, so far as Pina was concerned, is that an ordinary common-or-garden off-the-peg hydrophone can’t hear the very high-pitched clicks employed by the Chilean dolphins; it can only hear the middle range of frequencies. And so she and her wonderful supervisor had something specially made for the job.

A few weeks later, Pina duly arrived aboard Mollymawk with a massive suitcase containing ‘her baby’ – a state of the art hydrophone capable of hearing everything from alpha to omega. She subsequently spent three weeks with us; and during this time we learnt that there’s a lot more to recording dolphin sounds than just dangling the hydrophone over the side.

For a start, you first have to find your dolphins.

Happily, having just passed a couple of weeks in the Golfo Almirante Montt and the neighbouring channels, we had a very good idea of where to go looking for our quarry; but, even so, we could have saved a lot of time and employed our days much more productively if we had been able to use a ‘spy in the sky’.

The distance travelled by an echo-location click is only about 500 yards/metres – and that’s a best case scenario, with the animal pointing its kit so that it ‘looks’ straight at the hydrophone. So, there’s seldom much to be gained by just dangling the thing in the water and hoping for the best.

With the aid of a drone we could have located the dolphins from aloft, and this would have saved us the time and trouble and fuel involved in patrolling round and round their domain. Unfortunately, since a waterproof drone costs in the region of $ 3,000 US, this is something which will have to remain on our list of daydream items.

As a general rule, we Mollymawks operate in a relaxed sort of a way. This is our home, after all, and our way of life. We’re here, doing this ‘alternative’ thing, twenty-four hours a day, forever and ever; so, except when we’re crossing oceans, we don’t have hard and fast rules about watch-keeping and other chores, and we don’t have a timetable; and we certainly don’t run the ship as if it were a research vessel.

With Pina aboard, all that changed. Suddenly, we were a team of scientists and pseudo-scientists, each one with a responsibility. From the moment that we weighed anchor each morning we were on duty. The sea around us was divided into quarters, with one person responsible for each area; and when dolphins were sighted – at that moment things went into over-drive.

As soon as dolphins were sighted, Nick, as helmsman, was required to get us to them, come hell or high water or rocks or tide-rips. And the dolphins of this vicinity do love rocks and tide-rips…

Meanwhile, Caesar and Roxanne and Pina would fly to their various stations, all of which were involved with turning on the hydrophone and deploying it. I guess one day there will exist a hydrophone which is as simple, in its operation and its feedback display, as our echo-sounder; but at the moment the state of the art consists of the precious microphone – a thing so fragile that we aren’t even allowed to tap it – and this ‘gubbins’ is joined to the thinking end of affairs by a stout shielded cable.

“Look after the cable,” said Pina, shaking her fist at the dog, “because if it gets damaged, by a claw or a paw, for instance, and the water gets inside, that’s it: finished.”

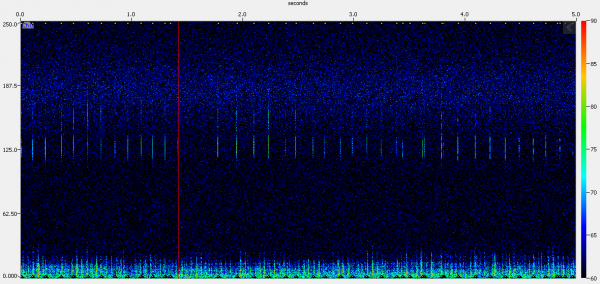

Having crossed the deck from the hydrophone, the cable enters the box of tricks. First it connects to the amplifier; and the output from the amplifier passes first through a ‘high-pass filter’ and then through a ‘low-pass filter’ (these being devices used to get rid of extraneous noise). Then, having been amplified and filtered, the signal is divided in two. One half goes to a set of headphones, whose use enables the operator to ensure that we have ‘action’, and the other half goes to the Data Acquisition Card.

The hydrophone is the equivalent to our ears. What it’s actually hearing, or receiving, is minute differences in pressure. These pressure oscillations, causing the device to vibrate, are converted into differences in voltage; and it is these differences in voltage which are transmitted, continuously, up the precious cable.

Now, if you’re au fait with computers (which I’m not) you’ll know that computers can’t read analogue signals, which are continuous; so they have to have the message translated into digital format. This is what the Data Acquisition Card does. If the hydrophone is the ears, the Card is the part of the brain which converts the variation in voltage into something which our minds can begin to comprehend and call sound. It samples that continuous electrical impulse coming up the wire and feeds the computer ‘snap-shots’. This is also the means by which a loud-speaker turns the electrical impulses from a recording of Beethoven’s Ninth or Stairway to Heaven into something which we call music – but in that case the ‘shots’ are sampled at the rate of less than 96,000 per second, whereas the Data Card associated with our hydrophone brings them in at 500,000 per second.

As I said, it’s all pretty high tech. And it’s just as well that our crew includes Caesar, who thoroughly understands and enjoys all this stuff.

Once it’s been recorded by the Data Acquisition Card, the information can be displayed by the computer in a variety of ways – but that part of the business comes later. Before we could see and analyse the signal, we had to record it… and therein hangs the tale of our adventures.

Having located the dolphins and contrived to get amongst them, we then had to stop the boat. This is because our hydrophone is not of the ultra-ultra sophisticated type. Or rather it is, in terms of its acoustic range, but it’s not a towable device. If we were to tow this particular hydrophone then all that we would get is a recording of the sea rushing past the super-sensitive ‘ear’. Now that she’s seen the potential, Pina hopes someday to equip the good ship Mollymawk with just such a thing – but at the moment it doesn’t exist, and its creation will be the work of many months and many thousands of dollars.

So, in the meantime, the procedure which we adopted was along the following lines:

Pina: “There! There! They’re over there, Nick! Go over there!”

Nick: “Over there… Hmmm… I’m not sure if there’s enough water for us over there… but we’ll have a go…”

Poppy: “Woof! Woof!”

Pina: “Caesar! – the lap-top! Roxanne! – get ready to deploy! Jill! – where are they?”

Jill: “Um, well…. I last saw them near that rock…”

Pina: “Don’t take your eyes off them!”

Jil: “Well, I… They sort of vanished…”

Pina; “There they are! Quick! Stop the boat!”

Poppy: “Woof! Woof! Woof!”

Nick: “What’s the depth?”

Roxanne: “I’m not sure. Someone’s turned off the echo-sounder.”

Poppy: “Woof! Woof! Woof!”

Jill: “We can’t anchor here! The current’s running at three knots!”

Nick: “Someone tell me the depth!”

Pina: “There they are! Stop the boat! Deploy! Deploy! Have you remembered to turn it on, Roxanne? Are you getting them, Caesar?”

Caesar: “Umm… Well, what I’m mostly hearing is the current rushing past the hydrophone…”

Poppy: “Woof! Woof! Woof!”

Pina: “Jill, have you got some ID shots? Are we anchored?”

Jill: “It’s too deep to anchor. We’re in sixty-five metres. Yi! Mind that whirlpool, Nick! Gosh, if the engine quits now….”

Pina: “We need to turn off the engine. It’s too noisy. And what’s that signal? SOMEBODY’S TURNED ON THE ECHO-SOUNDER…!”

Despite the fact that this kind of comedy routine occurred on a daily basis – on an hourly or bi-hourly basis, indeed – we did managed to get some very worthwhile recordings of Chilean dolphins (Cephalorhyncus eutropia). This is a species which has apparently only been recorded once before.

We also got some brief recordings of Peale’s dolphins (Lagenorchynchus australis), another species with which scientists seem to be very little acquainted.

On another note – we also became fairly knowledgeable about the narrows which lead into the Golfo Almirante Montt, and specifically with the Santa Maria Channel and the White Narrows and the Islas Delfines (as we now refer to them).

On our first passage from the channels into the golfo we were quaking in fear of the mighty currents which, according to the cruising guide, can be encountered in both the Santa Maria Channel and in the Kirke Narrows. And, after all, Skyring and Kirke – those intrepid surveyors who were the first to pass this way – certainly had plenty of adventures. Besides spending a few hours with their schooner being spun in circles in the eddies, they were also carried alongside an islet and pruned it with their main boom.

Familiarity breeds contempt, however, and after a fortnight of chasing dolphins amongst the islands in the mouth of the Santa Maria channel we were merrily bucking the Spring tide or dropping anchor in the midst of it all. We even travelled along the Ooshy-Slooshy Channel (properly called the Ushucoico) which had once seemed impossibly perilous.

I guess you could say that we are now experts in the passage of this particular system of narrows – and our conclusion is that the waters here behave according to their own whim, and you can forget about watching the tide table. It almost never relates to what’s actually going on.

One thing I will say, and that is that I would not ever want to come through here under sail alone, because there’s almost always either no wind or far too much; and whatever wind there is is totally unpredictable.

Oh, and the whirlpools are impressive.

To return to the subject of the dolphins – I suppose one might ask the question, “Why is this important?”

Why do we need to know what noises the various species of dolphin are making?

One part of the answer is that we can’t seem to protect things effectively unless we understand them – unless we love them, indeed. And we haven’t been doing a very good job of loving and protecting the dolphins which live on the Pacific coast of South America.

When the British Admiralty commissioned two ships to survey these waters, in the early part of the 19th century, the men involved in the undertaking saw dolphins, porpoises, whales, and seals in abundance wherever they went. Where, nowadays, can one see such abundance?

Nowhere.

Tierra del Fuego and the Chilean channels are renown as an untouched wilderness, but although the trees are still standing and although the greater part of this region is still without roads or buildings or other man-made contrivances, we certainly haven’t left the place untouched.

Where have the whales and the dolphins gone?

Concerning the whales, no one really knows the answer. Last year, more than three hundred sei whales washed up in the inlets of the Golfo de Penas (about a third of the way down the Chilean coast). We still don’t know why they died. Some have suggested that the disaster was caused by a poisonous algal bloom, or ‘red tide’, which may have infected the plankton which the sei eat – but as yet there has been no evidence for such a bloom.

Others suggest a more sinister cause. Could the navy have been deploying some sort of weaponry on this coast? Or could there have been some kind of industrial seismic survey taking place?

And if not that, could it be the salmon farms which are to blame?

That’s just the seis.

Where are the hundreds of humpbacks which used to frequent Admiralty Sound and the area, in the Straits of Magellan, in the vicinity of Isla Carlos III? To be sure, there are still humpbacks to be seen in this vicinity in the summer – and the area has been declared a sanctuary; so there is hope! – but I imagine that it will be a long time before anyone will experience the wonders that those early explorers recorded:

“This part of the Strait teems with whales, seals, and porpoises. While we were in Bradley Cove, [almost opposite Cabo Froward, on the south side of the Magellan Strait quite near to the new sanctuary] a remarkable appearance of the water spouted by whales was observed. It hung in the air like a bright silvery mist and was visible to the naked eye, at the distance of four miles, for one minute and thirty-five seconds.”

Philip Parker-King

“Thousands of porpoises and seals were seen sporting about as we proceeded on our way [through the Shag Narrows]. Whales were also numerous in the vicinity, probably because of an abundance of the small red shrimp, which constitutes their principal food.”

William Skyring

“During a remarkably calm night, we were frequently startled by the loud blowing of whales between us and the shore [in Admiralty Sound]. We had noticed several of those monsters on the previous day, but had never heard them blow in so still a place.”

Philip Parker-King

“On the following day, while going with Mr. Kendall to Wollaston Island [in the Cape Horn archipelago], we passed a great many whales, leaping and tumbling in the water. A blow from one of them would have destroyed our boat, and I was glad to cross the Sound without getting within their reach.”

Philip Parker-King

It might be said that the reduction in the numbers of whales and seals was a direct result of the explorers’ discovery and their reporting of what they found. Only five years after his first visit to the region, Robert FitzRoy wrote –

“Whales frequent the surrounding waters [of the Falklands] at particular seasons, and they are still to be found along the coasts of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego though their numbers are very much diminished by the annual attacks of so many whale-ships. … Seals are now rare.”

So it would seem that the whales were brought to the verge of extinction by commercial activities in the 19th and 20th centuries. Although they still haven’t come close to recovering their numbers, there are already moves to end the moratorium on whaling – and thus we need to be vigilant in defending that ban.

Seals, meanwhile, are also fairly rare – although I dare say they might be more abundant on the exposed rocks and islets which guard the outer coasts of the Chilean archipelago. In times past there were men who were mad enough to risk life and limb hauling the animals off these wave-swept rookeries, but since seal blubber is no longer a commodity much sought after I imagine that, in those perilous locations, they are now reasonably safe. Or at least, they would be if there were still enough food for them to eat.

Yes, that’s the crux of the matter – man has fished the seas to such an extent that, seemingly, there just isn’t the food to allow the seal populations to return to their former numbers.

What goes for the seals probably goes for the birds too. What is there for the penguins to eat now that man has scraped up the sardines? We hear that on the Pacific coast of North America, seabirds have been washing ashore with their bellies empty. Perhaps it’s happening down here, too – but nobody knows, one way or the other, because down here there’s no one to see it.

That brings us back to our first question: Why do we care whether there are recordings of the Chilean dolphin, or Burmeister’s porpoise, or the Hourglass dolphin, or the Spectacled porpoise?

Why do we care whether they still exist when most people will never have the chance to see them?

The answer is that besides having their own intrinsic place in the world, these animals are ‘ambassador species’. They’re the lithe and lovely top rank of the pyramid of life in the sea. They’re the marine equivalent of tigers and rhinos.

If the whales and dolphins are not well, the chances are that the whole castle is coming tumbling down. And if we can get people interested in saving them, we might be able to save the lot – and save ourselves into the bargain.

Don’t forget that every other breath that you take is created by the sea; and if the sea dies – if the sea ceases to be able to function as it does now, absorbing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen – there’ll be nothing else for us to breathe.

So… Where have all the dolphins gone? And have they really gone, or is it just that nobody much is patrolling this patch?

As far as one can gather, the answer is that, the region being not much frequented, there certainly is a dearth of information; but the information which is available does seem to show a significant reduction in numbers.

For example, I think it’s been a long time since anyone reported seeing thousands of “piebald dolphins” such as Pringle Stokes saw in the Golfo de Penas in 1826. This was evidently a description of either Comerson’s dolphins or the Southern Right Whale dolphin, both of which are now rare.

We’ve never seen a Right Whale dolphin (or Flour Bag dolphin) anywhere; and we haven’t seen any ‘Commies’ since we left the Atlantic.

Friends of ours who’ve been cruising this region for the past twenty years and who take a strong interest in such things tell us that they have never seen either species north of the Straits of Magellan, and even there they’ve seen them only rarely.

Some folks suggest that the scarcity of dolphins is connected with the salmon farms, the effluent from which is known to poison the adjacent waters. Could it be that the detritus from the incarcerated fish and from the antibiotic-laced food which is their lot have polluted the waters to the extent that other marine life can no longer inhabit the area?

Perhaps. But it may be that the reduction in the numbers of dolphins has a much more direct cause.

You’ve surely heard of the Mexican Vaquita and of how this dolphin has been pushed to the very brink of extinction by the fact of being accidentally trapped in nets. Well, it seems that American purse-seiners working off the coast of Chile have been likewise implicated in the incidental capture and murder of dolphins. It would seem that dolphin-friendly tuna is a myth. The boats find their quarry precisely because the dolphins show them the way; they deploy their massive nets, encircling everything; and if the dolphins don’t find their way out, that’s too bad.

Even that’s not the end of the story, because, of course, the big tuna-slaughtering boats are not working in inshore waters, and they’re certainly not in the channels. So, who’s harming the dolphins here?

According to various locals with whom we have discussed the matter, the culprits here are their own fisherfolk.

The thing is, seal meat – and dolphin meat – is free. Nowadays, the dolphins and the seals are protected by law; but there’s no law on the high seas, and even in the channels there’s no police force. It would be completely impossible for the Chilean authorities to patrol these thousands of miles of waterway.

Now that the dolphin is a taboo animal, no one is bringing it to market; but we hear that its flesh is still being used to bait crab pots.

Most Chilean crab is exported, as is the salmon. So, if you want to do your part in trying to protect the dolphins and whales and seals, and in trying to preserve life in the ocean – both for its own sake and for the sake of all life on earth – vote with you purse: Boycott tuna; Boycott farmed salmon; Boycott king crab.

Let the Chileans know that their most valuable commodity is their unique and very wonderful environment whose protections offers the potential for millions of dollars worth of eco-tourism.

If you should happen to be visiting Punta Arenas you might like to actually put your money where your mouth is, in that respect, and make a trip on a boat which takes people to see the whales. One such is www.expeditionfitzroy.com

We know nothing about this company beyond the fact that it runs trips to the whale sanctuary and through the Shag Narrows to a very spectacular tidewater glacier. If its existence can encourage the Chilean government to see the value of protecting the local environment, this most certainly has to be a good thing.

Jill: “You know, there seem to be far fewer dolphins around when it’s raining.”

Pina: “Oh, you think so, do you?”

Jill: “Yes, I think they don’t like rain. I think they take one look at the weather, on a day like this, and then they all go back to bed. They live on the bottom of the sea, you know, in their mansions… with the mermaids… In fact, there seems hardly any point in our keeping watch…”

Pina: “If I hear any more of this nonsense I shall take away your hydrophone! Get back on the foredeck at once, and do your scientific duty!”

Jill: “Right away, Ma’am! Sorry, Ma’am! Such a notion will never cross my imagination again!”

As we head north we will be aiming to find all eight species of dolphins reputed to be found in Chile’s waters. So far as the Peale’s, the Duskies, and the Chileans go, I think we stand a good chance; and we can also hope for the best regarding the Comerson’s, the Southern Right Whale dolphins, and the Hourglass (only recorded twice – and with two very different recordings). But so far as the porpoises are concerned – the Spectacled and the Burmeister’s – I think it may be too late. So far as we can gather, no one has recorded any sightings of either of these two since the seventies.

However if you’re cruising this coast and you happen to see something which meets the description, please be sure to get some photos…!

The science world seems to be largely oblivious of the fact that there exists a huge navy of sail-powered vessels whose crews are generally very interested in studying and protecting the marine environment and who, together, have the potential to provide them with all manner of information – if they’d only let us know what information they want… With a view to harnessing this capacity and expanding the quantity of information available, we’re aiming some time soon to create a data base where yotties and other seafarers can upload information about cetacean sightings.

But there are only four of us, and there are only a certain number of hours in the day, so it hasn’t happened yet…

In the meantime, if you’re cruising the Chilean coast and you see something interesting, please drop us a line. Likewise, if you’re interested in the project and you can afford to finance the purchase of a waterproof drone, or if you want to get involved in funding the development of the all-singing, all-dancing towable, broad-frequency hydrophone – we’d love to hear from you.