Ushuaia – a town in denial?

The prettiest thing about Ushuaia is its setting. But there are actually lots of beautiful mountains and bays all throughout the Beagle Channel, so how did this place come to be ‘the chosen one’? Why is there a city here?

Ushuaia means something like East-facing Bay. The Yaghan indians who once lived on the shores of the Beagle Channel named most of the coast in this same manner; pretty much all of their place-names end in waia (bay) because their life revolved around travelling from one such place to another. And they weren’t exclusive with their names, so there may have been half a dozen other ushuaias in the region. This one has kept its name and found fame for just one reason: It was the place chosen by the Reverend Stirling and his young side-kick, Thomas Bridges, when they wanted to establish a Christian Mission, bringing the gospel to the indians.

It was on the hill behind these houses, on the south side of the bay, that the missionaries founded their model settlement.

Bridges and Stirling had first tried establishing a base on the coast of Navarino Island (on the opposite side of the Beagle) at a place known as Laiwaia. However, there was not enough land there to accommodate the settlement which the missionaries envisaged, and nor was the harbour adequate for their supply boat, the Allen Gardiner. Thus it was that they crossed to what is now the Argentinian shore.

In January of 1869, Reverend Stirling took up residence on the Ushuaia peninsula in company with a small band of ‘tamed’ Yaghan. But six months later he was recalled to the Falklands having been appointed Bishop of South America…

For the following year the indians were left to cope by themselves, with only occasionally visits from Thomas Bridges, but in October of 1871 that bold young man brought his new wife and their babe in arms and settled his family in Tierra del Fuego – and for good.

As his son, Steven (Esteban) Lucas Bridges was later to observe, “[at that time] the nearest contact with civilisation was the Chilean convict settlement at Punta Arenas, a hundred and twenty miles away over impassible mountain ranges and across the Magellan Straits”.

Picture the scene which faced the young Victorian gentle-woman as she arrived in her new home:

“As they were rowed ashore from the Allen Gardiner, this Ushuaia of which she had heard so much was strange and rather frightening. Behind the shingle beach the grassland stretched away to to meet a sudden steep [hill]. … Between the shore and the hill were scattered wigwams – half-buried hovels made of branches roofed with turf and grass, and smelling, as she was later to find, of smoke and decomposed whale blubber … Round the wigwams dark figures – some draped partially in otter-skins, others almost naked – stood or squatted gazing curiously. … On the summit of the thornbush-covered hill she saw her future home, Stirling House [as it had been named] – a bungalow of wood and corrugated iron. … Though it was now mid-Spring, snow lay about in patches and on calm nights ice formed in the sheltered harbour. …

In that country my mother was to spend the greater part of her life.”

But it was okay, because she and her man had come here to do God’s work, and that knowledge sustained them and gave them an indefatigable, unstoppable confidence unavailable to those of us who only stand on our own two feet.

Looking north and west from her new home, Mrs Bridges will have seen nothing but snow-covered mountains on the far side of the bay.

This boat is now parked on the beach in front of the place where the Bridges lived. I’ve no idea what it’s all about, but it seems to fit the mood of this story.

This drawing, made in 1883, shows the Mission. The house on the far right is in approximately the same position as that now occupied by the Afasyn Yacht Club.

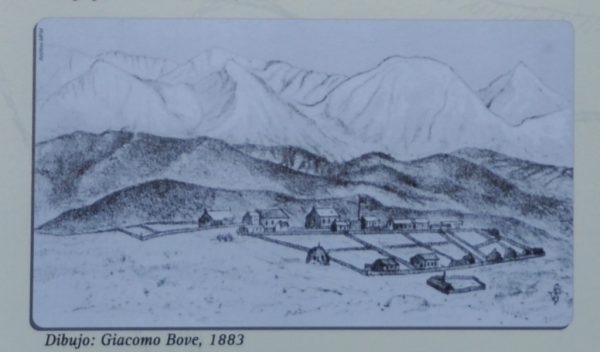

The two drawings were made by Giacomo Bove, the leader of an Italian naval expedition to this region. This one shows the Mission from the opposite side. The hills in the middle ground were destined to become the site of the city centre.

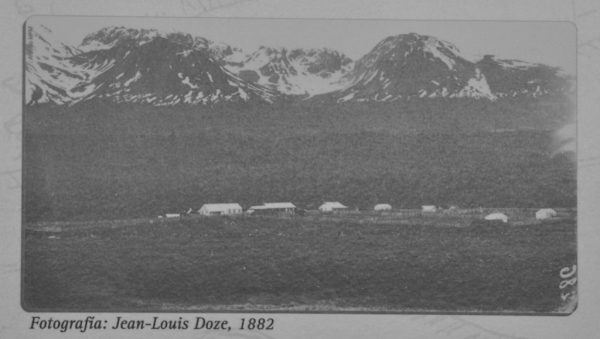

A photograph of the Mission from the edge of the hill, looking south-west.

Looking in the opposite direction, from roughly the same location, in 2016.

A notice on top of the hill proclaims the fact that here, on this site, an Anglican Mission was established “with the aim of evangelising to our ancestors” – a rather odd way of putting it, having regard for the fact that the Ushuaians are almost entirely of European descent. The other strange thing is that there is no mention of the main man.

The site of the Mission has now been fenced off. A monument (standing in approximately the place from which these last two photos were taken) pays homage to the “pioneer missionaries” but, again, without naming Thomas Bridges or any of the other settlers.

Funnily enough, I’ve found scarcely any mention of Thomas Bridges in Ushuaia – which is odd, because he really was the founding father of the town.

Would Mr and Mrs Bridges know the place now? And would they like what Ushuaia has become?

Lucas Bridges tells us that his father always understood that he was operating in a foreign land and feared what would happen when the rightful owners – or, as one might say, the new claimants – turned up. How would Chilean or Argentine officialdom behave towards this British family and their Yaghan protégées? At the time when the settlement was formed, neither Spain nor its ‘descendants’ in this realm had explored further south than the Magellan Straits, and the two rival powers had yet to define their borders – so he had no way of knowing to which nation he must eventually submit.

Sixteen yeas after the Mission was begun, in September of 1884, the unavoidable thing happened: The face of authority suddenly rocked up aboard a fleet of four Argentinian gunboats. Although they greeted the missionary and his family warmly, the navy made it clear that he must acknowledge their overlordship; and so the mission flag was lowered and an Argentinian one raised in its place.

A prefectura, or quasi-military base, was established on the northern side of the bay, at the eastern end of the site where the town was to be built. (This shore of the bay was known to the Yaghan as Alacushawaia – Steamer-Duck Bay – whilst the opposite side, where the mission stood, was called Tushcapalan. Lucas Bridges translates Tushcapalan as Kelp-Island-of-the-Flightless-Steamer-Duck.)

Unfortunately, the official founding of the town had a disastrous effect on the Yaghan. In the aftermath of the visit by the Argentinian navy the community was smitten with the measles, and within a few weeks half of the several hundred people were dead. The remainder were so weakened that they were unable to tend their gardens effectively. Being malnourished they subsequently became susceptible to other ailments, and as a result, over the course of the next two years, more than half of the survivors of the measles epidemic also died.

Thomas Bridges had for sometime been considering the idea of founding a cattle ranch where the newly-civilised indians could be given employment, and in the wake of this disaster, which became further exacerbated when a large maximum-security prison was built at Ushuaia, he moved from consideration to action. He set about acquiring the title to a large tract of land some thirty miles to the east of Ushuaia, at a place now known as Harberton.

Estancia Harberton was granted to the Bridges family by the Argentinian government expressly in recognition of their service at this frontier of the realm. So it does seem odd that the people in the City Museum haven’t even heard of Thomas…

There is, so far as I am aware, not one square or statue in Ushuaia commemorating the man who started it all. Instead, the town celebrates San Martin.

San Martin was the ‘liberator’ who led the people in their fight for independence from Spanish rule – but at the time when he was doing his stuff, Tierra del Fuego was pretty much off the end of the map. Independence was declared in 1816, some twenty years before Fitz-Roy came and explored the southern end of the continent with the Beagle – and that was long before this ‘uttermost’ part of the continent had been claimed.

Bridges’ eldest son, Despard, was the first European born in these parts, and this merits a mention in the City Museum, but Thomas and his wife seem to have sunk without trace.

One man who is commemorated in the town – by his family, at least – is a chap by the name of Luis Fique. Fique is alleged to have arrived in Ushuaia aboard those naval gun boats, aforementioned, and to have stayed to serve as part of the newly formed prefectura of Ushuaia.

According to the notice in the window of the shop which his descendants now run, Fique was the first Argentinian to settle here.

(Some writers claim that the family who worked with the Bridges at the mission were also Argentinian – albeit their name, Lawrence, contradicts that idea, and Lucas Bridges tells us that they came from England.)

The Fique family shop sells cuddly toys and buys US dollars.

Thomas Bridges died when he was only 56, seemingly from a haemorrhage of the gut. The year was 1898; and I doubt whether there remains a single building in Ushuaia which has stood since this time. Incredibly, the house in which the missionary and his family lived has been preserved – but it’s in Puerto Williams.

The church is probably the oldest surviving building in town, and the Bridges children would surely know it. But note that it’s that little church, on the right of the photo, that I’m talking about.

Lucas Bridges died in 1949, and the big yellow church is absent from photos taken in the early 50s.

Moreover, although they might recognise that little church, the Bridges boys would surely be confused by its surroundings.

It used to stand pretty much on the seashore. The flat land in front of the buildings has all been reclaimed.

Here’s a house which Lucas Bridges and his brothers and sisters certainly knew. Casa Beban was built in 1911 – but not on this site.

The place where the Beban’s house stood is now occupied by this creation.

No doubt the Bridges family were also familiar with the town’s bandstand, although it must also have been built many years after their departure to Harberton.

Whereas, in the time of the Mission, ships used to anchor in the bay, now they go alongside a big quay. In the summer the town sees a continual stream of cruise ships, and it can also accommodate fair-sized container ships and tankers. It has to, because, of course, everything that the citizens of this far-flung outpost of modernity need must be brought down from the River Plate, 1,400 miles to the north.

People sometimes ask, “Why is this town here, ‘at the back of beyond’?” – and the answer is that it’s here, and it’s big, because the government want it that way. Just as they stormed in on Thomas Bridges, thanked him very much, and founded the prefectura in order to stake a claim, so too, over the years, they have provided various incentives to encourage people to settle here.

Yes, it’s a strange place, this artificial city at the end of the world; and one of the strangest things about it is the fact that it claims to be the capital of the Falklands Islands.

How it can be the capital of somewhere which lies hundreds of miles distant is a bit of a puzzler… And that’s to say nothing of the fact that those islands are home to a people who claim allegiance to a different nation. Perhaps this is why the Bridges family have been swept under the carpet. If Ushuaia is the capital of a place which claims to be British, then it might be a bit embarrassing to have to acknowledge that the town itself has British roots, too.

Nationalism is a strange thing, and a dangerous thing, but few of us can withstand its pull. However, the irony is that Thomas Bridges was probably far less concerned than most of us with pride in the country where he just happened to have dropped into the world. After all, he was an abandoned baby – named for the fact of having been found on a bridge, can you believe! – and having left England at the age of 13, and having no family there, he can scarcely have felt any very strong ties with the place. He brought his children up to speak Yaghan and Spanish as well as English; and his descendants, having lived in this corner of the country ever since, surely have the most right of anyone here to consider themselves to be sons of this frozen soil.

But there – so far as the official history of Ushuaia is concerned, Thomas Bridges’ place of birth has tainted him; therefore, he doesn’t exist.

Speaking of nationalism – a notice on the wall of the port says that English pirates are forbidden to moor here.

Some Welsh friends have complained about this, as they feel left out…

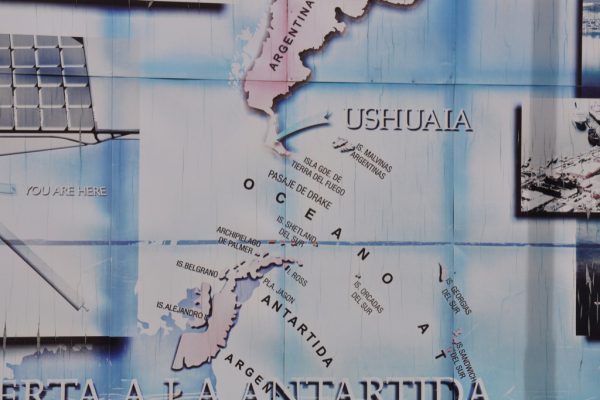

And then there’s this map, which is also on the wall outside the port.

As you can see, it shows Ushuaia at the end of the American continent. Between Ushuaia and Antarctica lies the Drake Passage and… nothing else.

One wonders how the Chileans feel about the fact that this part of their nation has been obliterated.

Argentinian tourists come to Ushuaia to have their photo taken at El Fin del Mundo – The End of the World.

So, if this is the end of the world, that place over there in the distance must be…?