A Rum do in the Cape Verdes

Back in ye olde days His Majesty’s Royal Navy used to experience a little bit of difficulty in recruiting sailors. Small wonder since the food was awful, the discipline was unbelievably severe, and the accommodation smelly, dirty and very cramped. There being few volunteers to live a life more dire than that of a convict, the navy took to grabbing men out of the fields and inns and even out of their homes. Needless to say, this workforce was not a very cheerful one. Desperate to maintain order over the rabble their Lord High Admiralships hit upon a canny scheme. Every morning each sailor was issued with a pint of rum. This Happy Hour may not have made the men willing and obedient, but it ensured that they were too drunk to get their act together and organise a mutiny.

In more recent times the navy has found that with clean ships and good food and clever advertising they can lure plenty of young men to run away to sea, but despite this they kept on handing out a free round of drinks each day, and it was only in 1970 that some busy-body committee of do-gooders brought about the abolition of the practice of converting each new recruit into an alcoholic.

Ever eager to preserve the traditions of the sea, the captain of the good ship Mollymawk and those of various other vessels in the cruising fleet have been doing their best to maintain the old custom of drinking large amounts of grog each day – and in Cape Verde they found a plentiful supply of material for this chore.

The smell of burning wood wafted towards us as we approached the derelict building, and with that aroma came another: a sweet, almost toffee-like scent. Passing along the front of the house, beneath its tall drystone wall and it’s gormless empty windows, we came to a small clearing littered with dried sugar-cane trash.

And adjacent to the clearing, tacked onto the house, we found the source of that smell: a wood fire blazing fiercely inside an open-fronted kiln.

The man tending the fire looked round in surprise as we approached and then nodded and smiled in greeting.

“Boa tarde”, we responded – but our Cape Verdean friends led us on, past the man and his oven, and inside a lean-to shed with a sagging, partly-broken-down roof.

Inside the lean-to, in the semi-darkness, another man sat next to a small alcove. All around him there were 44 gallon oil drums and glass jeroboams, and in his lap he held an exercise book and a pen.

“Boa tarde,” we said again, and I peered into the alcove. It was cut into the wall directly opposite that stone-built kiln with its hot fire, and from out of the wall a copper pipe protruded. Beneath the pipe there sat a big copper mug; and joining the two, in intermittent fashion, came drips of colourless liquid.

The man with the notepad smiled knowingly and, reaching down, he quickly swapped the mug for one of the big glass bottles. Then he held the copper vessel towards me.

I sniffed the mug cautiously, and handed it on to Nick.

The Cabo Verdeans all laughed. “Nao gust’ grogue?”

Difficult to answer that one without giving offence – but fortunately I had no need. While the men were laughing, Nick had first sipped, and then gulped, and then swiftly knocked back the contents of the copper mug. “Muito bom!” he pronounced. Very good.

Indeed, as he was forced to admit when questioned further, Cape Verdean “grogue” is the finest rum in the world – and this stuff that they made in Brava was the best of the best.

It was during our second visit to Cape Verde that we first discovered the rum makers. We were wandering aimlessly on the outskirts of a village in Ilha Santo Antão when we happened to come upon a strange and rather quaint scene. In a clearing on the edge of a field of tall canes a gaggle of young boys was chasing a pair of small skinny horses round and around some sort of machine.

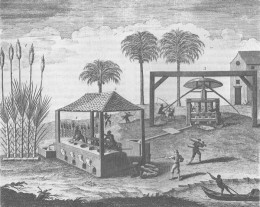

Closer inspection revealed that the horses were tethered to two curved wooden beams and that they were actually the driving force for the central mechanism, which consisted of a robust upright mangle. As we arrived on the edge of the circle the horses were ambling along, and the ragamuffin boys were idle. Two men, standing at the centre of operations, were sorting through a pile of stiff green canes. Then, while we watched, one of the men began to feed a couple of the canes into the mangle; and the boys all began to yell and swipe at the horses, and the horses began to heave in earnest at the timbers which they were obliged to haul in their perpetual perambulation of the machine – and a trickle of green liquid ran down from the mangle into a bucket.

We had just witnessed our first “trapiche” in action.

One of the kids scooped up some of the liquid from the bucket and hurried towards us, proffering the dirty plastic cup at our two small children.

One of the kids scooped up some of the liquid from the bucket and hurried towards us, proffering the dirty plastic cup at our two small children.

What would be the result of this, I wondered? A cold and a runny nose, like the Cape Verdean urchin’s – or hepatitis? The refreshment being foisted upon us was of an opaque green colour, and it was covered in froth. I was just wondering how best to excuse ourselves from this awkward predicament when Caesar (then aged 2) grabbed the cup and downed the entire offering. Then he licked his lips and asked for more.

Yes, it may have looked pretty awful, but it tasted good. It was pure, unadulterated and unrefined sugar cane juice.

Crushing the canes to capture their juice is but the first step in the creation of “grogue”, or rum. It is also the first step in the creation of sugar and molasses, and in the late 17th century the islands of the Caribbean would all have been littered with scores of “trapiches” exactly like this Cape Verdean example.

Crushing the canes to capture their juice is but the first step in the creation of “grogue”, or rum. It is also the first step in the creation of sugar and molasses, and in the late 17th century the islands of the Caribbean would all have been littered with scores of “trapiches” exactly like this Cape Verdean example.

By the 18th century, however, things had changed. Those Caribbean plantations were big business, and the technology supporting the industry had been vastly improved; by the 18th century most Caribbean sugar plantations were served by wind-driven sugar-mills.

While high investment and high returns in the West Indies swept England onward towards riches, power, an industrial revolution, and a vast empire, the Portuguese colonies stagnated – and none more so than the dry, barren archipelago of Cape Verde. The few valleys which could support crops, and which might have been used to produce food for a starving nation, were acquired by men who didn’t even live in the islands, and they were planted with sugar canes. But the profits won from farming these semi-arid terraces were small. Thus, the Cape Verdean rum industry – like almost every other aspect of its civilisation and culture – remained stranded in a time warp. Indeed, walking around these islands in the last years of the 20th century, we often felt that we had stepped back a hundred years or more.

Well, anachronisms such as the Cape Verdes cannot endure forever, and the islands are now being rushed forward into the 21st century. The unspoilt beaches of the eastern isles have been snapped up by the time-share sharks and the all-inclusive-holiday businesses; the ageless cobbled roads are being paved; the lateen-sailed fishing boats are now driven with outboard motors; television has arrived in the larger villages – and the “trapiches” are now driven by petrol engines. Or at least, some of them are.

The “trapiche” which we watched in action in Santo Antão, 16 years ago, is now motor-driven. So too are the ones on the island of Santiago; so too, some of the mills in São Nicolau, and at least one of the three in Brava. But whereas the majority of people in the third world are generally all too ready to throw up their old traditions and fling themselves into the crushing embrace of modern technology, some of the folks in the Cape Verdes have a more mature attitude. Untypically, for peasant people, some of the folks here can see that all is not well at the top of the slippery slope which leads to the place we call Western Civilisation; and they can see that their remote, untroubled villages, with their stone-built houses and their fleets of little fishing boats are better – or, at any rate, happier without many of our mod cons.

These same people are proud of their old animal-driven sugar mills, and while the wannabes have rushed forward to grasp at the riches waved by greater productivity, these few have contented themselves with producing quality instead of quantity.

The first distillery that we ever visited in Cape Verde was even more primitive than this latest one in Brava. Like the Bravense one it stood immediately adjacent to the “trapiche”, and it consisted of an open fire over which a cauldron had been balanced. Above the iron cauldron there was a collecting vessel, made of earthenware, and from this vessel the steam ran downhill through a copper pipe clad in bamboo jacket. Water led from a nearby stream ensured that the jacket remained cool, so causing the steam to condense, and the condensed liquid was collected and sampled by a group of solemn men who sat beneath a low, thatched canopy at the bottom end of the pipe.

Although it was associated with a semi-derelict house, the equipment at the Brava distillery was well maintained, and it was slightly less primitive than the arrangement we had encountered in São Nicolau. The stone-built range outside the lean-to contained two ovens, the first of which was sited below a big iron cauldron. This cauldron was virtually identical to the ones which were used in the West Indies (and which can still occasionally be seen, lying around on the ground, in villages in Antigua). The vast semi-circular bowl is used to heat the sugar cane juice which has been crushed in the adjacent “trapiche”.

When it is being turned into sugar the juice must be boiled for a very long time, but the rum making process does not require such a thick consistency. When the appropriate state has been achieved the syrup is ladled into barrels and fermented – and it was these barrels of fermented juice which stood around the room where the grog was being collected.

The second oven – and the one in use at the time of our visit – is the one which supports the still. This consists of a stainless steel container placed above another, smaller vat. The vat is fitted with a pipe allowing the fermented cane syrup to be poured in without the need to remove the stainless steel box – and it was the addition of a new helping of syrup which we had smelt as we arrived at the works; it produces an aroma like caramelised sugar.

From the distillation chamber the steam flows down a coiled pipe which winds its tortuous way through a water-filled trough. Again, as in San Nicolau, the water in the trough comes from a nearby stream which has been diverted to trickle through the cooler.

From the cooler the product runs down to drip from the end of that pipe, in the adjacent room – but that is not quite the end of the story.

Distillation is actually a fairly critical process, with the temperature of the fire being crucial in the creation of a consistent result. While we watched, the man guarding the pipe took out a little gauge – the gauge from a battery tester, as it seemed to be – and he measured the specific gravity of the liquid raining down into the copper cup. If it was too weak then the grog was tipped into the slops bucket. At first we thought that the workers – and their numerous friends and hangers-on – were to benefit from these (as it seemed to us) rather frequent accidents. We imagined that they would enjoy a “happy hour” like no other. However, in reality the slops just have to be sent round again, until the correct result is achieved.

Meanwhile, Manuel, the stoker, received frequent admonition: “Too hot!” “Too cold!”. He was constantly adding fuel or removing burning brands from the oven.

From each 200 litres of thickened cane juice the Bravense distillery produces 30 litres of very strong, top quality grogue. (Cape Verdean rum is always stronger than the West Indian equivalent, and that produced “by hand” in the traditional way, is the strongest of all.)

The annual harvest from this one trapiche, and from the pockets of sugar-cane planted amongst the onions and maize on the terraces in this one little valley, is about 2,000 litres of liquor.

The tradition of rum making – and rum drinking – is deeply rooted within Cape Verdean culture. Presumably the thousands of Cape Verdeans who emigrate to Europe and to the United States have to forgo the pleasure of making the stuff themselves, but wherever home distillation is legal they go ahead and do their thing. Thus, we have watched second generation Cape Verdeans in the distant isle of Principe (São Tomé) crushing canes through petrol-driven mangles and quaffing mugfulls of home-made grog. Indeed, in this poverty stricken land, with its high infant mortality rate and its low average lifespan, rum drinking is one of the few pleasures available. The kids join at an early age; and thus some die even younger than they might otherwise have done.

Back in Cape Verde, the grog produced on the hillsides has a much wider market. The men who operate the mill and the distillery are merely the employees of a rich boss, and although they will no doubt take home a small share of the harvest to their families the greater part will end up in the islands’ bars and in the cornershop grocery stores. Some will even make it to Portugal.

The “connoisseurs” with whom we cruised the islands tell me that there are a great many different types and qualities of Cape Verdean rum – and even I can tell, from a sip or even a sniff, that some are more like lighter fuel than Bacardi. Others, such as the hand-made stuff from Brava, are a great deal smoother than that well-known brand.

For those who are visiting the isles and want to try the stuff I recommend asking around in the market or in the corner shops. Bottled and labelled, the cheaper grog costs about 7 Euros per 750ml, but if you take along an empty 5 litre mineral water bottle and have it filled by a wholesaler, from a 44 gallon drum, the price comes down to 3 or 4 Euros per litre.

The better quality, trapiche-made grogues can cost as much as 9 Euros per litre even when purchased in the distillery, from the men doing the work.

If rum is not to your liking you may like to try the adulterated product, which is called ponche. Traditionally, ponche consists of “grogue” and “mel” – mel being the Portuguese word for honey and the Cape Verdean word for sweet molasses. (You can also buy “mel” by itself, in the market. It has a fruity taste which gets stronger as the stuff ages, and if you keep it for more than a couple of weeks it ferments.)

Nowadays it is also possible to buy coffee flavoured ponche and fruit flavoured ponche, but these are products which have been dreamt up especially for the tourist market.

Decidedly the best way to sample grog is with the locals – either in a grocery-store-come-bar, late in the evening; in a remote village, where someone is almost certain to call the footsore traveller over and proffer a glass; or as we did, on this latest occasion, in a traditional distillery. The Cape Verdean people are unsurpassable for their generosity and their hospitality, and our visit to the hillside trapiche and the still reminded us of other such visits, made 16 years earlier. Arriving, uninvited and unannounced, we seemed to provoke only a very minor stir, so that we imagined it to be a very commonplace event for our hosts, yet as we shook hands and left the men to their work, Manuel, the fire-stoker said, “I will remember this day for the rest of my life.”

And so, I am sure, will we.

With thanks to Jose (left) and Roberto (right) and Mickey (pictured above, with Nick) for taking us to see the distillery.