Birdlife in the Canary Islands

Which bird would you reckon is the most common in the Canary Islands?

Go on, have a guess.

The blackbird? No; there are lots of these – they are even more common than in Britain, I would think – but they are not the most abundant bird in the archipelago.

Some kind of seagull? No; there are surprisingly few seagulls here.

The Canary…? No…

The answer is the Cory’s shearwater (Pardela cenicienta in Spanish; Calonectris diomedia in Latin).

Despite the fact that they are so common here I would guess that many Canary Islanders never see a single “cory”, because these birds live on the ocean. They come ashore only to attend to their nests, and, even then, they only come during the deep darkness of the night.

Despite the fact that they are so common here I would guess that many Canary Islanders never see a single “cory”, because these birds live on the ocean. They come ashore only to attend to their nests, and, even then, they only come during the deep darkness of the night.

Cory’s Shearwaters

Cory’s shearwaters are found in the Mediterranean, in parts of the South Atlantic Ocean, and throughout much of the North Atlantic, including the area west of southern Britain. They are about the size of a herring gull or a yellow-legged gull, and like other shearwaters they spend their days gliding around just above the waves, searching for small fish or squid. As we cruise around the Canaries these birds are our constant companions. We are accustomed, as we cross the ocean, to having a shearwater or two skimming around in the vicinity, but here we find that there are almost always a dozen in sight.

Funnily enough, although we always watch them closely we have never actually seen a shearwater find anything to eat. I suspect that this is because they do most of their eating at night when the squid come up to the surface. Nevertheless, the birds tend to keep on flying tirelessly all throughout the day. On first acquaintance this seems to make no sense; indeed, it seems almost impossible. How can a bird afford to spend its energy flying around if it is not constantly refuelling itself? The answer is that the shearwater does not use its own energy to fly.

Energy Saving

The shearwater’s means of travel is not at all like that of their land-lubbing brethren, nor even like that of their remote cousins, the herring gulls. Land birds (with the exception of the larger birds of prey) flap their way through the air. Even the bigger seagulls – those masters of aerobatic flight – are apt to spend a lot of energy travelling from A to B. Shearwaters, like other oceanic birds, travel by means of the wind. In effect, they sail along, tacking from A to B in a pattern of swooping, gliding zig-zags. To the casual observer their flight appears haphazard, but in reality the birds are riding the air currents which the rolling waves create. Thus their energy requirements and their food requirements are much smaller than those of a “flapping” bird of similar size.

The “cories” have increased in number since our arrival in the Canary Islands, and this is because they have returned for their annual nesting season. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they have finished their holiday season. The business of raising a new chick seems to dominate the entire existence of the mature, breeding “cory” couple; they spend three quarters of the year in preparing their nest, hatching their one egg, and feeding and fattening junior until he is fit to join them on the ocean.

Home, Tweet Home

Cory’s shearwaters make their abode in holes and clefts in the cliffs, creating huge colonies – the avian equivalent of apartment blocks. The Canary Islands, with their tall, inaccessible, pocked cliff faces, present an ideal environment for this activity, and the surrounding waters, with their abundant sealife, seem to provide plenty of wholesome food for the young. Indeed, one wonders why the birds even bother to wander off across the ocean to Cape Town or the Straits of Magellan. Perhaps, like man, they reckon a change is as good as a rest. Or perhaps (being more realistic) they want to get their offspring away from the nesting territory and take them to pastures new. The young will spend five years growing to adulthood, and perhaps it is just as well if, during this time, they feed from some other larder.

Cory’s shearwaters make their abode in holes and clefts in the cliffs, creating huge colonies – the avian equivalent of apartment blocks. The Canary Islands, with their tall, inaccessible, pocked cliff faces, present an ideal environment for this activity, and the surrounding waters, with their abundant sealife, seem to provide plenty of wholesome food for the young. Indeed, one wonders why the birds even bother to wander off across the ocean to Cape Town or the Straits of Magellan. Perhaps, like man, they reckon a change is as good as a rest. Or perhaps (being more realistic) they want to get their offspring away from the nesting territory and take them to pastures new. The young will spend five years growing to adulthood, and perhaps it is just as well if, during this time, they feed from some other larder.

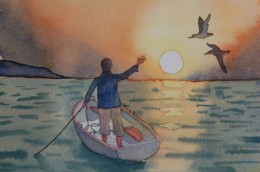

Having spent most of the day on the wing, in the evening the nesting shearwaters sit on the water in big “rafts” of several hundred birds. They are waiting for the sun to set and darkness to fall, for until the night is as black as pitch they won’t make a move towards the cliffs. Despite the fact that their nests are fantastically inaccessible, secrecy is paramount; the birds do not want to betray themselves and their offspring to any predator. However, when, finally, the time comes the birds give themselves away by making the most amazing sound.

Having spent most of the day on the wing, in the evening the nesting shearwaters sit on the water in big “rafts” of several hundred birds. They are waiting for the sun to set and darkness to fall, for until the night is as black as pitch they won’t make a move towards the cliffs. Despite the fact that their nests are fantastically inaccessible, secrecy is paramount; the birds do not want to betray themselves and their offspring to any predator. However, when, finally, the time comes the birds give themselves away by making the most amazing sound.

Vivaldi is to the Blackbird as Buddy Guy is to the Cory

One struggles to find a way of describing this weird noise. It is neither a mewing nor a cawing; it isn’t a song, and it isn’t a bit like any of the varied cries of a seagull. I suppose the best way to describe it would be as a kind of buzzing tune; a repetitive little two note melody which hardly sounds like a bird noise at all; it sounds like a cross between a cat’s miaow, an insect’s buzz, and the plucking of a tightly stretched wire. If that particular melange seems somewhat discordant… well, all I can say is that pretty much everyone who hears the noise finds it fascinating. Somehow, one cannot hear the shearwaters without smiling!

When we anchor below a roost we hear this sound for hours on end as the birds fly to and fro over the boat, yet it never becomes boring or irritating, and this is because every bird has a different voice. All hum roughly the same brief stanza, over and over again, but some sing high and some sing low, and some even sing to a slightly different rhythm. After a while, one can imagine that one recognises the different individuals as they fly over.

After they have laid their single egg a pair of shearwaters takes it in turns to sit in the burrow, one incubating by day and the other taking over during the night. Hence, the coming and going (and the calling) during the hours of darkness. The eggs hatch at the end of July, we are told, and then the parents spend the night bringing in food for their youngster. When the young are fledged (October / November, according to the book) the tribe will set off for South America.

Chubby Chicks

Unlike most birds following a migratory path, the shearwaters are able to feed as they travel – indeed, they are at home wherever they go across the ocean – but it will take the young birds some time to acquire the skill of foraging, and so before they are fledged their parents devote a great deal of their own energy to providing their youngster with a fat reserve. It is primarily for this reason that they can only manage to raise one bird each year.

We adore the shearwaters – but it would seem that the ancient inhabitants of these islands had a rather different attitude towards them. Less fascinated with nature – or much more closely involved with it, and living much closer to the thin line between survival and starvation – they used to risk their necks in climbing the cliffs in order to take the shearwater’s eggs. And not only the eggs but also the nearly-fledged birds. These were greatly valued for that precious, oily fat reserve.

Nowadays the shearwaters have no predator – and hence their super abundance. There are said to be 30,000 pairs breeding in the Canary Islands. Their numbers are limited only by the availability of nest holes and by the availability of food. With man continually plundering the seas, this second factor is almost certainly the one which sets the limit on their population size. Our liking for sardines has already brought about the virtual extinction of the South African penguin, which feeds almost exclusively on that fish, and our activities in the North Sea are endangering puffins and other seabirds. Eventually, as the situation worsens, a reduction in available food is bound to bring about a reduction in the population of shearwaters, too… but for the time being they are safe.

Nowadays the shearwaters have no predator – and hence their super abundance. There are said to be 30,000 pairs breeding in the Canary Islands. Their numbers are limited only by the availability of nest holes and by the availability of food. With man continually plundering the seas, this second factor is almost certainly the one which sets the limit on their population size. Our liking for sardines has already brought about the virtual extinction of the South African penguin, which feeds almost exclusively on that fish, and our activities in the North Sea are endangering puffins and other seabirds. Eventually, as the situation worsens, a reduction in available food is bound to bring about a reduction in the population of shearwaters, too… but for the time being they are safe.

Questions, Questions, Questions

The more I study these birds, the more I find myself wondering about their lives.

I look up at the cliffs, where I know that the birds are hiding, and I can’t see their nest holes. No excrement betrays the location; so what, I wonder, do they do with that?

And then I begin to think about that odd little song. We have only once heard it while we were sailing – at our approach, a group of birds began calling as they took off from their raft. Certainly, the birds do not generally call or sing while they are flying, so why do they do it near the nest site? Is it a collision avoidance signal which helps them to locate one another in the pitch darkness? Or is it simply a means of identifying themselves to their nearest and dearest in the burrow?

“Here I come. Here I come. Never fear, it’s only me.”

More than anything I want to know when do they sleep, for heaven’s sake? They spend pretty much all day on the wing, and then they seem to spend all night flying to and from the nest and feeding their chick.

Come to that, when does any seabird sleep? They don’t seem to sit on the water at night. They only sit on the water when it is too calm to fly.

Can they sleep on the wing? Imagine that: imagine being able to stroll around, side-stepping the wave tops, and riding the up-draughts, without even being conscious that you are out there…..!

But would newly- fledged birds really be capable of that?

Ospreys

By way of contrast, there are only 15 pairs of ospreys in the Canary Island archipelago. We have met one of this number – indeed, we have watched him hunt, and we know where he nests – but although we feel privileged to have seen this rare and beautiful bird, still he does not excite in us the same fascination as the common “cory”.

Jonathon Livingstone Shearwater

Yesterday, as we sailed along amongst the shearwaters, one of them began flying to and fro immediately ahead of the boat. Seabirds always find our boat confusing; it is an island that moves – which no real island ever does – and so they are apt to misjudge the way they pass and come closer than they might have intended. Sometimes they almost touch the rig.

But this bird had not only realised this fact, he had also discovered something else: he had found an up-draught caused by the wind flowing under the foot of our headsail and then rushing up behind it. He kept swishing to and fro in U-shaped passes. He did it twenty times in succession – and just for the kick, I am sure. The rest of the flock were shearing around in the usual (semi-conscious?) way, but he was wide awake and playing; he reminded me of the dolphins who ride at our bow wave.

And then he got it wrong and nearly touched us, and I could swear that his expressionless face showed surprise!

And then he got it wrong and nearly touched us, and I could swear that his expressionless face showed surprise!

These birds are so intelligent. And their lives are so utterly remote from ours. We see them, and we take them for granted – we tick them off in the book – but their way of life is so different that we cannot even begin to really know them.