Robinson Crusoe’s Isle (but not really)

When they pointed it out to us from the village, Selkirk’s Look-Out seemed to be not very far away. We had come ashore to do the official paperwork incumbent upon any new arrival to the Juan Fernandez islands, and we were not equipped for a hike. We had just one small bottle of water between the five of us and no food. Still, the path up the back of the valley did not appear to be very steep, and the distance was certainly not great.

Hardly had we left the rambling suburbs of the village than we began to revise our ideas on the matter of gradient, and by the time we reached the ruins of the castaway’s supposed abode, halfway up the hillside, we were ready for a rest. From the ruined stone hut, the path wound onward and upward to reach the little wooden gazebo that we had espied from the village – but this, as it turned out was but another breathing place. To reach the famous Look-Out we had to climb a set of giant, hand-hewn stairs; and then we ascended a narrow, muddy trail which zig-zagged up through the native woodland.

Finally, after two hours of exertion, we reached a saddle in the spine of the island. Astern of us lay the green of the forest, the red-brown of that eroded hillside where we had sweated up the steps, and, at the foot of the mountain, the sprawl of the village and the vast blue sea. The pier jutted out into the bay, and on the far edge of a flock of small boats lay a bigger one; a yellow one with two masts.

Cameras clicked as we gazed back whence we had come. And then we all turned to take in the view on the far side of the saddle – and five sets of lungs exhaled a gasp of surprise, and five spirits soared. “Wow!”

The western half of Isla Robinson Crusoe is as different from the east as the Sahara is from the Congo.

Well… okay, that’s an exaggeration, because the inhabited eastern half of the island is nowhere near so lush as the Congo Basin. But the further part of the western half is an orange-brown desert.

The western half of Isla Robinson Crusoe is a fantastic fairyland of jagged pinnacles and serrated peaks. Bottle-green forest clothes the steep slopes adjacent to the Look-Out. Soft shades of apple-green and olive cloak the folds which hang above the sea, describing a thin cover of seasonal scrub. Rambling away to the west, the contours are splashed, here and there by patches of rust; and at the farther end, the island is a fiery mass of orange and brown touched with patches of white.

Add another, smaller island, reaching away like the peninsula that it once was, aeons ago.

Pin it all onto an azure sea, with a delicate fringe of white lace trimming the dark-chocolate, shadowed cliffs of the tableland.

Frame the picture between two insanely steep hillsides – one on either side of the saddle – such as only Walt Disney or Dr Seuss could have invented; and that’s the view which filled the gaze of Alexander Selkirk as he awaited rescue.

A True Adventure Story

Alexander Selkirk was a pirate. Or rather, he was the sailing master aboard a ship which was licensed as a privateer – and that’s much the same thing. He came to the Juan Fernandez Isles aboard a ship which was one of two under the command of William Dampier (1652-1715).

Dampier is a fascinating character. By the time that Selkirk came to be cast-away in Juan Fernandez, Dampier had already ‘done a hundred things’ that most people never even dream of, and he was all set to do a hundred more. If he were alive today he would probably be a cruising yotty, but since such a pastime had not been invented he did the next best thing; he joined a pirate ship. He appears to have had little interest in the usual piratical pursuit, of amassing a treasure through robbery; rather, he wanted to see the world. He had a passion for examining everything that he saw during his voyage, and he was one of the very first travel writers. In his journals (which were more precious to him than liferaft rations) our hero described everything from the feeding habits of flamingoes, the breeding behaviour of turtles, and the nutritional value of breadfruit, all the way through to the workings of the pirate brotherhood, the appearance of the Australian aborigine, and the administrative organisation of the sultanates of the Philippines. He also provided us with our first description of the Juan Fernandez islands.

By this time, in the 17th century, the Juan Fernandez islands were well-known to the pirates, for they formed an ideal base for operations along the Spanish-owned coast of Chile and Peru. Dampier therefore made several visits to this HQ before, eventually, tiring of the pirate game, he embarked on the merchant vessel which would carry him across the Pacific. After a great many exciting adventures and several close encounters with death, the vagabond finally made his way home to England; and here, some six years later, he published his first travelogue.

William Dampier’s book turned him into an instant celebrity, and his fame allowed him to approach the Admiralty with plans for another world-girdling Voyage of Discovery. Alas, however, the explorer and writer proved to be no great shakes as a captain. Perhaps the manners of pirates were even more brutal than those of the 17th century navy, or perhaps the well-bred officers simply disliked being mastered by a yokel. In any event, the voyage was a disaster and Dampier was subsequently found “not fit to be employed as a commander of any of his majesty’s ships”.

Within the year our man was commanding again, but this time the job was more suited to his CV. He was in charge of two privateers – the St George and the Cinque Ports – and he was to go a-roving on the old coast with which he was familiar. Unfortunately, however, the captain of the Cinque Ports fell out with Dampier while they were in Brazil and set off alone for the Pacific. And (coming, at last, to the point of our story!) it was he, and not the erstwhile commander-in-chief, who abandoned Alexander Selkirk to his fate.

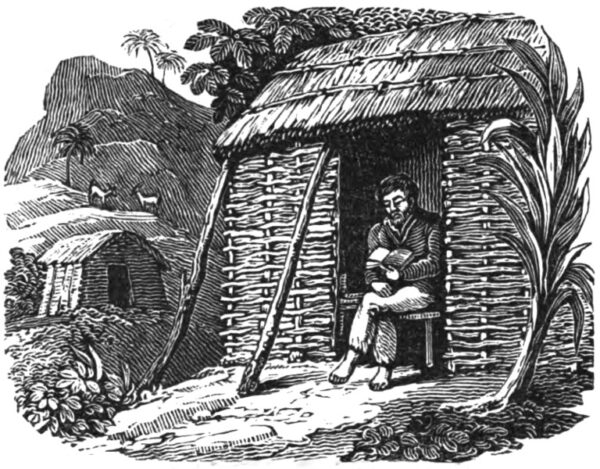

There were really only two ways of becoming the captain of a privateer. There was Dampier’s way – the way of the celebrity – and there was the more usual one of being the biggest bastard on the ship. Captain Stradling was evidently the latter sort of man. By the time his vessel reached Juan Fernandez she was in a very poor state, and her sailing master declared that he would rather be marooned on the isle than continue aboard her. By this remark he evidently meant to persuade Stradling to spend a few weeks refitting the ship, but the ruthless captain took him at his word. Although Selkirk tried to apologise, he was dumped on the beach with nothing but a musket, some powder and shot, an axe, a knife, a cooking pot, and a Bible.

Interestingly enough, Alexander Selkirk was right: the Cinque Ports subsequently foundered off the coast of Colombia and most of her crew drowned. The survivors spent some time in an insalubrious Spanish gaol, but (sad to relate) Captain Stradling not only survived the sinking but, as an officer, was also soon released by the Spanish and made his way back to England.

This proves that there is no God.

Of course, Selkirk was not to know any of this, and he spent a miserable time alone on the island, regretting his rash words and praying to the sky.

At first, Selkirk lived on the beach, feeding on fish and lobster and on seal-pups, but after a little while the seals drove him inland. There were at that time, many thousands of seals in the bay, and they were more than capable of holding their own against one lone man who was eager to preserve his shot and powder. Thus, Selkirk moved into the valley and began to feed on the cabbage trees and on the feral goats whose ancestors had been marooned by the islands’ discoverer. (Juan Fernandez had tried to found a colony here, but the people abandoned the place when the going got tough.)

Whether Selkirk really lived in a stone hut half way up the valley is a moot point. The locals are sceptical about this idea, pointing out that the saddle, a mile or so beyond and above the ruined hut, would actually be a silly place for a Look-Out. The view is splendid, but it is not all encompassing. The hills which frame it would have prevented the castaway from scanning the ocean to the east – and it was from the east that salvation would surely come.

The locals suggest that Selkirk must have lived at the eastern extremity of the island, at the top of the cliffs. Even so, and notwithstanding the fact that he probably rambled all over the island, I suspect that the sailor spent most of his time in the valley above the familiar bay; because he was not eager to attract the attention of just any old ship which might happen to be passing. Indeed, when a Spanish ship stopped at the island, the Scotsman was obliged to hide in a tree. He reckoned that to be captured by the enemy would be a fate even worse than lonely exile. What Selkirk awaited was the arrival of a British pirate ship or privateer; and knowing that any such ship which passed this way would be bound to visit the anchorage, if only to take on water, he had no reason to scan the sea in any other direction.

The ruins, half way up the hill towards the Look-Out, describe the outline of a lowly misshapen hut such as a solitary sailor might well throw together if he were not planning on staying longer than he could help. One of the locals told me that he reckons it to be the ruins of a powder magazine, but I am sure that it is not. Every magazine that I have ever seen has been far more robust, with the bottom part sunk into the ground and with walls ten times thicker; and besides, there is no gun emplacement nearby. The hut is conveniently near to a small stream of water – the only stream that we saw during our rambles over the island – and it affords a view of the anchorage whilst still allowing the occupant time to flee if a ship with the wrong flag should appear. Selkirk could not have chosen a more suitable place!

By his own account, from the day that the Cinque Ports sailed away, Selkirk was absolutely desperate to get off the island. The poet, William Cowper was greatly moved by the castaway’s tale and has him uttering these lines:

“I am monarch of all I survey.

My right there is none to dispute;

From the centre all round to the sea,

I am lord of the fowl and the brute.

O’ solitude, where are the charms

That sages have seen in thy face?

Better dwell in the midst of alarms

Than reign in this horrible place.”

Anyone who has ever visited it will agree that the island whereon Selkirk was marooned is far from being horrible. It is utterly delightful. The sailor need never fear hunger or thirst; he would never be too cold nor too hot; and the scenery is beautiful. Visiting the place almost 200 years later, Joshua Slocum climbed to the Look-Out and read the commemorative plaque placed there some 30 years before by the officers of a British warship, and he marvelled:

“The hills are well-wooded, the valleys fertile. … There are no serpents and no wild beasts. … Blessed island of Juan Fernandez! Why Alexander Selkirk ever left you was more than I could fathom.”

But Slocum was old. He had already sailed all over the world in various ships; and he had already been married twice and had four kids. Alexander Selkirk was a young buck of just 24 years. And he was not of a reclusive nature; he was not the man to sit and meditate on the beauty of the ocean or to commune with God. His only prayers were supplicative; he begged and pleaded for rescue.

By his own account, from the day that the Cinque Ports sailed away, Selkirk craved the sound of other voices. Probably, he also craved the company of a young woman, and the occasional sup of beer mightn’t have gone amiss.

Four long years passed. And then who should rock up but our old friend, William Dampier!

Dampier was now making his third circumnavigation, this time as the master of a privateer called the Duke. The captain of the Duke was one Woodes Rogers, a renown pirate but a man who had never previously sailed in the Pacific – and thus he relied heavily on Dampier’s advice. After a terrible rounding of the Horn, with the Duke driven as far south as any vessel had previously gone, Dampier guided the ship to his old pirate haunt. And on their arrival at the island – and having noted that there were no other ships in the anchorage – he was astonished to see smoke rising from a fire on the beach. On going ashore he was met by a lean, bearded figure clad in goatskins.

If Dampier was surprised to find his old shipmate still alive, Selkirk was simply dumbstruck. Finally – finally! – after four years, his prayers had been answered; and he found that he couldn’t even utter a word. Speech had left him.

160 years later, Robert Louis Stevenson used Selkirk as the prototype for his castaway, Ben Gunn. Gunn has been abandoned on the Treasure Island by pirates, and when he is eventually rescued by the heroes of the adventure he cannot speak. But the Scottish sailor’s story had already been borrowed, long before this, in his own lifetime – and therein hangs our tale.

Myths and Legends and Lies

At the Look-Out, we found a wooden plaque installed by the Chilean forestry commission, Conaf; and, nearby, we found the bronze plaque laid there by the officers of HMS Topaz and seen by Slocum. We also found a plywood plaque put in place by the crew of a visiting yacht. It said, “For our childhood hero, Robinson Crusoe”.

When Daniel Defoe penned the tale of Robinson Crusoe, he borrowed very heavily from the account of Selkirk’s adventure – but he set his story elsewhere. Crusoe is a sailor aboard a ship which is wrecked some time after passing the outflow of the River Orinoco, in Guyana; and, indeed, Defoe even gives coordinates for the island whereon the survivor is cast up. The coordinates are those of Tobago.

The flora of Crusoe’s isle is Tobago’s. And the man who Crusoe rescues from a cannibal stew-pot has arrived at the island, with his captors, in a canoe. No canoe could ever reach the Juan Fernandez islands, for they lie more than 300 miles offshore. Meanwhile, Defoe also tells us that the mainland coast is visible from his castaway’s isle.

There is absolutely no question that the Juan Fernandez islands are not Robinson Crusoe’s isle – and yet…

It was back in the 1950s that the Chilean government decided to cash in on the Robinson Crusoe myth. Until that time, the principal Juan Fernandez islands were known as Mas a Tierra and Mas Afuera (Nearer-the-Land and Further-Out). Now they are called Robinson Crusoe and Alexander Selkirk – and the irony is that the island carrying his name is not the one where “the real Robinson Crusoe” lived!

The marketing trick succeeded – the name-change put the Juan Fernandez islands on the map – but, in truth, there was no need to go inventing stuff. As we have seen, the place now known as Robinson Crusoe has a rich history all of its own. It also has its very own flora and fauna, its own very lucrative little fishing industry, its own island-born community, and a unique and spectacular landscape. All this, on a spike of volcanic rock smaller than many of the Caribbean islands.

At Juan Fernandez, the true story is actually very much more impressive than the legend.

Thank you x What an extra-ordinary place to have seen-I shall now go and reread Robinson Crusoe with a very different perspective!

Read, William Daimper, a Pirate of exquisite mind.