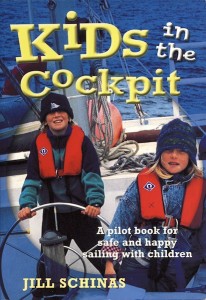

40 black-and-white photos and line drawings

40 black-and-white photos and line drawings

Paperback, 246 x 171 mm, 192 pages

Published by Adlard Coles Nautical

ISBN 978-0-7136-7229-3

RRP £14.99

Scroll down to see how to buy the book.

Kids in the Cockpit is the culmination of 14 years of practical research and record keeping which began when Caesar was a newborn baby.

Having, myself, been sailing ever since I was in a carrycot I was well aware that the sea always has

something new to teach us, but I hardly imagined that I had anything to learn about boating with babies. It seemed a bit of a non-subject. As my mother once said, when some other new mum asked her for advice, “There’s nothing to it. Just stick them in a lifejacket, and off you go.”

Well, it took me about ten minutes during one brief outing aboard a friend’s boat to discover that boating with babies is not “nothing”; it is actually jolly hard work.

In the wake of this discovery I tried to find a book on the subject of sailing withchildren, but the only books that I came across were of no use at all; they seemed to have been written retrospectively, by women whose kids had pretty much grown and flown. Such writers could hardly be expected to

recall the difficulties of breastfeeding in oilskins or the anguished cries of a youngster abandoned below while Mum helps to put in a reef… So I began to write my own handbook, keeping notes on a daily basis and recording all the ins and outs of boating with babies.

As my kids grew, so did my manuscript. It grew in volume and it grew in scope as I jotted down thoughts about lifejackets, recorded anecdotes about our misadventures in getting ashore, and scribbled down ideas about entertaining and educating children aboard a cruising yacht.

After 14 years I felt that enough was enough – already the notebooks filled a locker – and so I shaped them into a book and posted it off to Adlard Coles. They were delighted with the quality of the work but not with the quantity… and so they pruned the mass until it was sufficiently slender to fit on the bookshelf.

Kids in The Cockpit deals with every conceivable aspect of sailing and cruising with children from babyhood through to the teenage years. It’s all here, between the covers of this one volume – and if you find that it’s not there you can write and ask me for more information!

Safety is the subject of the first chapter. After you’ve read the tales of drama and the discussion of the various different types of lifejacket available you’ll know the difference between a 100N aid and a 150N jacket, and you’ll be able to decide which kind of lifejacket is best for your child. You’ll also know which sorts to avoid:

A lifejacket is the sailor’s very last chance when all else has gone dreadfully wrong and, as such, it must be adequate for the purpose. The trouble is, as I have already hinted, the same piece of kit is generally expected to serve at least two other functions: that of safety aid on a rough ride ashore in the dinghy, and that of protecting the child while he plays, either under oars or on the jetty. It may also be in regular use while the yacht is at sea…

The lifejacket issue is a complicated one. Many parents – ocean cruising parents in particular – decide to ignore it. Following Ostrich Policy they buy their child the cheapest second-hand buoyancy aid they can find and then stow it away in a locker, under the warps and fenders. “After all, it’s only

for an emergency, and we won’t be having one of those.” (Oddly enough, these are also the sort of people who enter the lottery each week.) …

During their experiments in the pool Caesar and Xoë particularly like testing the gear to see if it will roll them onto their backs.

When the names were changed, and the thing which we knew as a buoyancy aid suddenly became a 100N Lifejacket, manufacturers started trying to build these low volume aids in such a way that they would perform according to the old-style definition of a lifejacket. That is to say, they aimed to give their 100N aids the self-righting capabilities of the more efficient 150N jackets. In an effort to achieve this, the modern 100N Lifejacket is unevenly built, with more buoyancy on one side of the chest than the other. Some manufacturers seek to give the impression that their 100N jackets will, indeed, do the trick, but I have yet to come across a 100N Lifejacket which will self-right my kids.

The first, most obvious problem with an auto-inflating aid is that it might not inflate. If your child has pulled on the toggle which manually activates the inflation trigger and has neglected to own up to this demeanour (perhaps not even being aware that the CO2 cartridge is a once only device) then the

lifejacket will certainly not inflate when next called upon to do so. To be fair, deflating the jacket and putting it back inside its protective cover is a task which would defeat a very small child – but it is well within the scope of a seven year old.

The safety chapter also contains information about other ways of keeping your child safe, and it takes a look at the ways in which other full-time sailing families cope with this issue.

A parent should cultivate the habit of looking for quayside ladders, or any other means of getting from the water. Do this in every new port and encourage your children to do the same; ask them, if they are old enough to understand – “Have you decided where will you climb out, if you slip?”

Most children are unaware of the difficulty that they would have in climbing even onto a floating pontoon. If circumstances permit, have them jump in and find out. Even the relatively simple matter of getting onto a boarding ladder may be beyond a small child. … If you keep your boat in a marina and do not have a ladder permanently mounted on the boat, consider the possibility of nailing one onto the jetty.

Kids in the Cockpit is packed solid with tips and with true stories – first-hand accounts, for the most part – which provide further food for thought:

We had hardly dropped anchor off the little village of Tarafal before a crowd gathered. We were so close to the shore, it being steep-to, that we could have conversed – except that the sound of the waves dumping on the stones would have drowned the attempt.

They were not particularly big waves and there was no surf; just the one line of short, steep waves which kept rearing up and then dumping.

While we watched and considered the matter nervously, a small open fishing boat appeared on the scene. Without the least hesitation her crew headed her for the shore, and a moment later they were hauling the boat up the beach, with the help of their friends.

Nothing to it. Now it was our turn.

We dressed the kids in their lifejackets – the full works: 100N aids inflated to become pukkah 150N Lifejackets. We boarded the dinghy and half a dozen strokes carried her to the shore.

Nick swung the stern onto the pebbles – the safest way of landing if you have passengers in the stern – and as the transom touched the stones, the boat stood up in the air and turned a somersault…

Without wishing to be too much of a kill-joy, I should also like to point out that whilst the seafaring child should be taught to swim, and at the earliest possible age, the ability to doggy-paddle across the width of a swimming pool is almost irrelevant in a seaway. Indeed, a child’s increasing competence and confidence in the pool or at the beach can easily promote a false sense of security. Only this morning I received new evidence of this fact when Roxanne (6), on being told not to climb on the pulpit, said, “I don’t care if I fall in. I can swim, now.”

She can swim about 50ft.

Having dealt with such things as lifejackets, harnesses, and child-overboard drill the book then goes on to consider the safety of the vessel itself. Is your boat ocean-worthy? And is the deck clear of the kind of clutter which can endanger a small child?

While we are on the subject, more important even than the position of the mainsheet is the manner in which the crew allow the boom to cross the boat. If the boom is allowed to go flying across the boat, in the style that a racing dinghy is gybed or put about, then one will eventually lose either the mast or the kids. Or both.

So far as kids are concerned, falls aboard the boat are far more common than falls overboard. One thing which all yachts have in common is a couple of gaping “manholes” in the deck.

Having set the deck to rights, we proceed below:

Even in less exciting circumstances the average yacht’s cooker is a tool of the devil. It is much lower than the household cooker – well within the reach of a staggering baby’s inquisitive paws – and when the child grabs hold of it, it gives; it swings away from him. Even if the cooker is not in use this is bad news for the baby. As he topples and lets go, the beast lunges back at him and clobbers him below the belt. If the kettle is atop the stove while this duel ensues, the prognosis is even less good.

Oh, I detest gimballed cookers! Once, while I was innocently walking through the cabin of a yacht which was rolling along, the gimballed cooker lurched so violently that the cake which I had been baking burst out of the oven, shot past my legs, and landed upside down on the floor on the other side of the cabin. (It was only half-cooked and was quite unrecognisable as a cake, but the crew ate it anyway; sailors will eat absolutely anything.)

Chapter 3 of Kids in the Cockpit deals with the boating baby. Everything is covered; everything from dealing with his nappies, and doing without a pushchair, to stowing the baby in safety while you dash forward and drop anchor. The Law of Sailing with a Baby is explained at length… and, as ever, the gory details are interspersed with anecdotes. There is also a useful list of 50 things to do with a toddler to amuse him.

Babies are hard work aboard a boat, but older children make great sailing companions – or at least, they can do. Whether they grow into midshipmen or mutineers depends very largely on how they are handled. Chapter 4 of Kids in the Cockpit provides a light-hearted look at the psychology involved in ensuring that your young crew turn out right, and offers practical ideas for instilling a love of sailing.

Just in case your kids have not yet reached that happy state there is also a section devoted to entertaining press-ganged infants.

Identifying things is another time filler and a first class habit to encourage. Birds, jellyfish, seaweed, dolphins, clouds, stars…. headlands. You will need to carry reference books to enable the child to identify the flora and fauna and ephemera. The identification of stars and of headlands is a first step towards navigation.

For my part, I would steadfastly resist all requests from the crew for shipboard TV, videos, Gameboys and the like, and if we were weekend sailing I would resolutely deny my child access to the yacht’s computer (if any) for all but navigational purposes. Surely, one goes sailing to get away from such things? … In my young day (she croaked) we never had enough power to be thinking of having televisions on a boat. Or at least, my Mum said that we didn’t…

Of course, the best way to entertain a child and simultaneously to turn him into a sailor is to give him his own command. Yes, every “boating baby” needs a dinghy. Chapter 5 of Kids in the Cockpit deals expressly with this issue.

Although there are people whose penchant for snazzy accessories extends even to their children’s toys, yachtsmen are more typically inclined to think that any old rubbishy dinghy will serve the purpose of a children’s dinghy. Figures well known and respected in sailing circles have been heard to recommend “one of those very cheap beach toys” or have suggested that “the cheapest Campari will do,” but I say it will not; it most certainly will not. Toy boats are not designed for yachting and your child is far more likely to get into trouble if his command is a piece of junk, with no thwart, whose only means of propulsion is a pair of silly little plastic paddles. Anybody with any spunk or with the least desire to roam around and explore would be bound to get into trouble in a boat (so-called) which simply cannot be rowed properly. Moreover, your young seaman can hardly be expected to learn any worthwhile skills aboard one of these liabilities.

Rowing boats are all well and good, but the ideal first command for a child is a sailing dinghy – and if he is to have a sailing dinghy your child will need sailing lessons, too.

Fundamental to the ability to sail is an understanding of the fact that it is the wind which makes the boat go. Pretty obvious, you might think – but not to a small child. Whenever I had the helm of our Wayfarer my dad would tell me to watch the burgee: “Watch the burgee! Watch the burgee!” – on and on he went, like some demented parrot. Being an obedient child, I did as I was told and looked up at the little flag fluttering at the masthead, but really I thought that Dad ought not to distract me in this way; he ought to be encouraging me to look where I was going.

Eventually, my father must have realised that I had no idea of the burgee’s function, and so he explained: “Jill, the burgee shows you where the wind is coming from.”

This moment would surely have been the turning point in my sailing career if I had understood the relevance of the information. However, at this tender age I was not even aware that the wind was the boat’s driving force. When teaching children to sail, take nothing for granted; start with the obvious.

Chapter Sicks deals with the unpleasant subject of mal de mer – both the child’s and your own.

When you are already feeling ill, stifle any desire to yawn or cough. These two things both increase the likelihood of losing lunch and dignity. Keep warm, but do not get too hot. Eat, but do not over-eat. Sip tea or fruit juice, or whatever appeals, but avoid alcohol, beer in particular. And whatever you do, DO NOT GO BELOW. Do not even go below to use the loo; use a bucket, come what may. If pride comes before a fall, prudishness comes before an equally unpleasant event. If you do not use the bucket for the one business, you will certainly soon be using it for the other.

For heaven’s sake do not ask your child if he is feeling sick. Auto-suggestion is a very powerful force. If you suspect, just get him off the bunk cushions, fast.

Finally, the last chapter of the book covers the subject of cruising far afield en famille.

Would-be adventurers are often very worried about the safety aspect of taking their kids out into the wide blue yonder: Cruising safety, like any other kind of safety, is a matter of perspective. Yotties are not the first people to have taken their kids into an unforgiving, alien environment. The pioneers who crossed America and those who sallied forth from the African Cape journeyed, as we do, beyond the reach of outside assistance. They faced hostile natives. At least we, as a rule, only face hostile seas. If we want to be absolutely sure that our children are safe, then we must keep them cocooned in cotton wool. Keep them away from playschool, in case they catch meningitis; keep them off the street, in case they get run over or abducted. In fact, now that I come to think of it, perhaps the cruising lifestyle is actually safer than the landlocked one! My children are seldom exposed to those particular risks, and nor is it likely that they will die in a car crash.

The other big issue for parents is their children’s education.

Parents are generally very concerned about their child’s schooling, but did you ever stop to ask yourself about the purpose of the exercise? What do you actually expect your child to get from going to school? In short, for what purpose is he being educated? The way in which you tackle the business of home schooling will depend on how you answer this question.

Now that I have experienced home schooling, I would never dream of sending a child to school.

Make no mistake: sailing and cruising with children can be difficult at times, but when all is said and done I believe that the benefits and advantages far outweigh the hardships:

Yachting offers a range of adventure even broader than a fairground and can meet the needs of everyone, from the tot who finds a static ride on the merry-go-round utterly thrilling, to the teenager getting his kicks on the cyclone. From drifting along on the placid waters of a sheltered estuary to fighting for survival in a Southern Ocean blizzard, yachting has it all.

Cruising is a fantastic life style for kids; I can think of none to rival it.

Cruising kids have the benefit of growing up with both parents always on hand and are witness to the ways in which we cope with whatever life may lob in our direction, whether it be fixing the engine, salting a glut of fish, appeasing customs officials, or riding out a storm. The cruising lifestyle demands an independent attitude, and it is presumably for this reason that cruising kids grow up to be free-thinking, self-confident creatures.

Due to the limits imposed by the publisher, Kids in the Cockpit touches only briefly on the subject of cruising afar with teenagers and coping with their education. Anybody with questions not covered in the text should drop us a line, using the contact form, or post a comment here.

Kids in the Cockpit is copiously illustrated with line drawings and black and white photographs.

More Information

For more information see Jill’s website.

Kids in The Cockpit has received some very favourable reviews on Amazon UK, with all readers awarding it five stars. Our American cousins seem to find it a little harder to understand, but it is still rated “worth reading”.

Kids in The Cockpit is not available via this website, but can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon US, or from the publisher.