Cape Verde – São Vicente – Mindelo, Part I

Cruising Notes given in good faith, but not to be taken as gospel

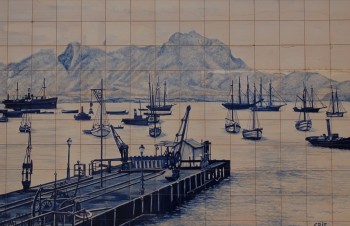

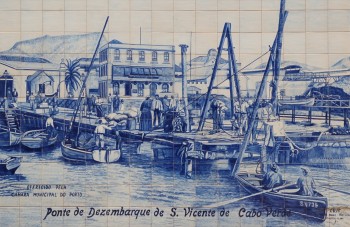

Mindelo, capital of São Vicente, is the second largest town in the Cape Verdes and the busiest port. Nestled in the north-eastern corner of a huge enclosed bay known as Porto Grande, it offers better shelter than any other harbour in the entire archipelago – but if you arrive here in the winter months then you may not appreciate this fact. Throughout January, February, and March the Porto Grande is blasted by a wind which hurtles down off the mountains to the north, so although the water remains flat you still need good ground tackle – you may even need a second anchor at times – and you will probably find the row ashore quite challenging.

Long Ago…

The wind may blow, but the waters remain calm in the winter months. The northerly swell never reaches into this cosy nook. The bay is aptly named, too – one hundred small coasters might anchor in here and still there would be room for more – yet despite all of this, throughout the first four hundred years of the islands’ history the place remained unoccupied.

How can this be?

Not a Drop to Drink

The answer to the question is very simple: there is almost no ground water anywhere in São Vicente. For centuries the only people to set up camp in São Vicente were subsistence farmers and fishermen. The farmers made use of the annual rains to harvest a crop on the highest hill. Then, when the harvest was gathered in, they moved away. Some also brought their cattle here and left them to wander at will and forage as best they could until they were wanted for the table.

Meanwhile, the fishermen based themselves in Porto Grande and at São Pedro, a very much smaller and even more windswept bay situated on the south coast of the island.

It is said that these part-time settlers had to bring their own water with them from the neighbouring island of Santo Antão.

Santo Antão is another story. Lying little more than five miles away, on the far side of a super-windy channel, it presents a complete contrast with its neighbour. Whereas São Vicente is a dainty pile of pyramids sculptured by the wind, Santo Antão is a fortress, massive and strong.

Whereas São Vicente’s barren slopes make it almost useless as a provider, Santo Antão is responsible for the production of most of the grogue and much of the veg and fruit to be found in the Cape Verde islands.

São Vicente is simply the biggest of a little group of straggling islands – simply the largest of a few pieces of irrelevant frippery – whereas Santo Antão is solid and serious, standing guard at the end of the chain.

In past times Santo Antão was undoubtedly the more important of the two sisters – if islands bearing the names Anthony and Vincent can be termed sisters…

Now, although the allegiance between the islands is just as strong, the roles have been reversed. Whilst Santo Antão still produces the food, the younger isle is the one that makes the money and calls the shots; and it’s all due to an Englishman.

An English Town

For centuries the Portuguese had been trying to encourage settlement on São Vicente, if only to stop some foreign power from setting up camp on the island. In 1624 a fleet of 24 Dutch vessels, with more than 3,000 crew, was found taking shelter in the bay, and pirates and enemy privateers also used this place as a base for their activities. Despite all this, it was not until 1795 that the Portuguese government was able to force the establishment of the first colony here. It consisted of 25 pairs of slaves – newly emancipated for the purpose, one assumes – who were taken from the island of Fogo. They were housed in a dozen tents which were erected on a site which is now occupied by the town’s main church. (You can see it from the anchorage.) By 1825 the village is said to have had more than 200 inhabitants, many of whom had come from Santo Antão, but a drought occurring in that year sent them scurrying back across the channel to the other isle.

Defiant, still, of the obstacles which a settlement here must face, the authorities continued to seek ways of encouraging a new colony, and since Portugal and England were allies they were very pleased when one John Lewis, representative of the British India Company, turned up to survey the island.

The year was 1836, and although it would be many a long year before steam took over from sail, the writing was on the wall. Steam-ships could keep plodding onward when sailing ships sat becalmed; they could blast their way through the doldrums; they could keep on going when the wind blew against them… but only if they could get enough coal.

The East India Company was looking for a coaling station half way down the Atlantic; and in Porto Grande they found the perfect place.

The Golden Age

Such was the excitement in the islands regarding this proposed development that permission was given to transfer the capital to São Vicente! Seemingly, there was even less going on at Praia (Santiago) at this time.

In the event, this transfer of power and authority never actually occurred. A palace was erected – a splendid pink and white structure, similar to other Portuguese colonial palaces – but the governor eventually decided not to take up permanent residence here.

The fledgling settlement was given the name Mindelo in commemoration of a beach-landing made in the Portuguese town of that name during the recent reconquesta (when Portugal threw off the yoke of Spanish rule).

In 1850 the Royal Mail Packet Line began bringing coal into the island for resale to ships heading south, and in the following year another British company known as Patent Fuel set up a second depot. The principal owner of this second company was one John Miller, and he won a place in history. The area occupied by his bunkers and offices is still known as John Miller, and one of the coasters plying the islands is also named in his honour.

Other British companies also set up shop here and in 1884 the India Rubber Gutta Percha company began the installation of submarine cables. These eventually ran, via Mindelo, from Africa to the USA.

With so much money flying around, the pint-sized town of Mindelo was blessed with elegant Victorian houses and public buildings, and a superb market place was built. There were oil lamps on every street corner and a neat and tidy square, complete with trees and flower beds, was built just a stone’s throw from the port.

But whence came the water to irrigate the flowers – or, for that matter, to supply the needs of the people?

It came from Santo Antão, still.

Water came by the ship-load from the tiny village of Tarrafal, on the south coast of Santo Antão. It was stored in a big tank standing just behind the church. The tank is still in existence and a bronze statue of a peasant woman occupies the place where the people used to go to fill their jars and barrels.

By 1880 the town had more than 3,000 residents and drought was no longer a worry, or so it seemed. The people had broken their ties with the land and it was foreign money which paid for their bread and butter – and for their schools, their library, their bakeries, butchers, marching bands and so forth. When things grew tough for their fellow Cape Verdeans the Mindelense, at least, would be able to able to keep on going. While the peasant farmers died of hunger on neighbouring Santo Antão, the new urban class would break open their piggy-banks and buy imported food…

So went the theory – but reality, when it hit, was rather different.

The Collapse

Shipping through Mindelo reached its busiest time in 1889 when almost 2,000 ships called at the coaling station. After that the town’s prosperity began to fade. A large part of the blame for the decline must go to the Portuguese government who applied such heavy taxes that the ship-owners switched their operations, choosing to refuel at Las Palmas and Dakar instead of Mindelo.

And as ever, of course, it was the workers who bore the brunt of the crash. The rich simply moved their money and their businesses elsewhere.

In 1891 2,000 workers lost their jobs as the coal stations began to reduce the size of their operations.

By 1910 the town was down on its knees and the poor were receiving aid from foreign charities.

Two years later, 4,000 unemployed coal workers staged a peaceful protest in the town square, demanding – quite simply – to be fed.

Eventually, in 1917, the council decided to provide the very poorest citizens with one free meal per day. Unfortunately, however, this actually worsened the situation. When they heard that there was free food to be had in Mindelo hundreds of starving people came hurrying in from the other islands…

Begging: The Family Business

By now the golden city had degenerated into the sort of place that yotties would certainly not want to visit. Vessels arriving in the port would be promptly surrounded by a fleet of bum-boats whose occupants sought to sell fruit and to beg for alcohol, cigarettes, and food. Ashore, the streets were grimey with coal dust; sewage lay in the gutters; there were more beggars to contend with, and there were also great numbers of prostitutes.

As a Portuguese yotty once remarked to us, in Mindelo scrounging from sailors is a traditional occupation. To this day we are still a target for boat-boys and beggars – (one beggar, on our most recent visit, rudely grabbed my arm and demanded that I give him money to buy himself a coffee!) – and to this day Mindelo also has far more prostitution than the other islands; and far more venereal disease.

From Bad to Worse

The people of Mindelo are rather different from their fellow Cape Verdeans and they have always been held, by those others, to be something less than holy. In 1934 they compounded this view by organising the only insurrection ever to have taken place in this country. Driven by hunger, they ran amok, looting the shops and warehouses for food.

No longer directly dependent on the arid land, the people were still not able to survive when the going got tough. Contrary to their rosy expectations, they didn’t have the money to buy imported food and the droughts which hit the islands in the 1940s are reputed to have killed thousands of them. Others fled away to São Tome, to work like slaves on the cocoa plantations. Some reports say that the population of the town fell by 30% at this time. Others claim that it actually went up because so many starving peasants came here from the other islands in search of non-existent jobs.

Salvation

Things didn’t really begin to get better until the 1970s, when Amilcar Cabral and his African compatriots won independence both for Guinea Bissau and for the Cape Verde islands. For the next thirty years or so the country survived on foreign aid and on monies sent home by emigrants living in Europe and the USA.

And then, suddenly, European people began travelling far and wide for their holidays. Someone spotted this bunch of tropical islands, and tourism arrived to rescue the country from its lean and hungry past.

Although the majority of tourists stay in Sal, São Vicente is the island which seems to have bagged most of the foreign money, somehow, and her citizens are the ones whose standard of living has been most affected, rising quite radically in the past 15 years. Indeed, the town appears to be experiencing a revival, of sorts. To be sure, there are still some poor people around. The fishermen and the women selling vegetable on the street still have a rather lean look about them. But the majority of the people now eat well, dress in clean clothes, and own a mobile phone and a TV. Some also own a shiny new car (bought “on tick”) and can afford to party the night away in one of the many new bars and restaurants.

Of course, the question still remains as to whether this is true nirvana or just another bubble which will burst with the next spin of the wheel…

For more information about the Cape Verde islands, take a look at our other recent articles about the archipelago:

- General info:

- Sal

- São Vicente

- Boa Vista

My friend: Joao Baptiste in Praia had an Uncle and Aunt in Midelo. Samuel and Isobela!..Joao took me to their home in Mindelo. Joao was an Engineer de Macina on Rincao (A Tuna Fisher Boat. Samuel was 104 and Isobela 98. They told me of beind Employed by a Cardiff Coal Company for many years as clerks in their office. I worlked as a Volunteer at SCAPA Praia.Sociadad/Co-operativa.Amilcar Cabral.Pescador. Artisanal. 1982-1985. I.m ex Royal Navy Armourer and a sailor!

Fascinating stuff. And I think it’s not often that Cabo Verdeans live to such a ripe old age. Thank-you for sharing this, Gordon.