Caribbean, Part V – If it’s Monday it must be… Saba

Having planned to spend only three days in Nevis, we eventually tore ourselves away after a week. Our next stop was Saba, which is only a day-sail away, beyond St Kitts and just beyond Sint Eustatius. When the seeing is good, as astronomers would say, ‘Statia and Saba are both visible from the anchorage off Pinney’s Beach.

Having endured a fairly windy and rough time in Nevis, with some mildly exciting beach landings, we subsequently found ourselves leaving the place on a morning of flat calm. We drifted away, each of us in turn narrowly avoiding an intimate embrace with a fancy mega-yacht anchored further off, and it was only once we had managed to limp out from under the lee of the island that we found any wind worth mentioning.

Out there, downstream from the venturi which accelerates the wind passing between Nevis and her big sister, we fell into a useful force four. The sun shone down; the two boats romped along. Everything was really rather pleasant.

Even after Mollymawk‘s mainsail tore (again), the day was still a golden one; but then, as we passed ‘Statia, the sky clouded over and the wind began to blow a little harder. Soon we were creaming along with the sea lapping at the side deck (always one of my favourite moments) and the loss of that ol’ mainsail was neither here nor there; we wouldn’t have been able to keep it up anyway. We were doing a steady 8 knots.

Saba

Johnson had already visited Saba many times and knew the place well, so it made sense, as the two yachts drew near to the island, for us to let him take the lead. The old salt had already predicted, pessimistically, that we would not be able to stop – “Four times out of five you can’t, you know; it’s just too rough” – but I had likewise made it clear that Mollymawk, at any rate, was stopping, come hell or high water. I had been wanting, for almost 20 years, to visit this place!

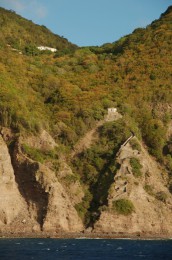

The reason for Johnson’s negative attitude becomes obvious when one looks at the chart of Saba. The island consists of one small extinct volcano – it even has a crater at the top – and it is round. When the wind is blowing hard (as it had been for the past week, and as it had now begun to do again) the volcano does not provide much of a lee. Both the wind and the waves go tearing round the place as if they were hardly aware of the obstruction.

Clearing In

Entrance formalities in this Dutch-owned island are fairly relaxed, but yachts do still have to clear-in. In order to perform this chore we needed to visit Fort Bay, which lies on the south-western side.

Johnson had told us that there was buoy off Fort Bay. (According to his account, it was laid – by no less a person than the prime-minister – for the exclusive use of the yacht Cherub… but according to Doyle (writing in his Leeward Islands Cruising Guide) the buoy is there for the use of any yacht clearing in or out of the island.

We spotted the buoy alright, but the sea was so rough that getting from the moored yacht to the shore in our dingies would have been impossible. Nor was the scenery in this part of the island at all alluring. On the contrary; the lofty mountain, wih its many pinnacles and the soaring cliffs made for a fantastically dramatic backdrop, but the settlement which lay at their feet, acting the part of village, was actually a tiny industrial port. From an artistic point of view, it ought to have consisted of a line of colourfully painted houses, together with a picturesque church and a row of palm trees, but actually it lacked any of these essential features being equipped, instead, with oil tanks and modern warehouses.

(If you do manage to get ashore – either by making use of the mooring or by returning, at a later stage, in your outboard-powered dinghy – you may like to note that opening hours for the authorities are said to be from 0800-1700, Monday through to Saturday. You can check in and out at the same time, estimating the number of days of your stay.)

Ladder Bay vs Johnson’s Nook

Cherub led the way, without further ado, round to the western side of the island. Here we discovered a line of mooring buoys running all the way from Ladder Bay (in the south) to Well’s Bay. The ladder, at the aforementioned place, actually consists of a set of stone steps which lead all the way up to the settlement, far above the sea, inside that extinct crater. I would dearly have liked to climb them – but there was no hope of getting ashore today, in this rough weather.

While we hummed and haaed over the discomfort factor involved in lying in this rather wild place – and while, further to this, we haaed a bit more over the choice of setting our own anchor or trusting to Dutch safety standards and Dutch hardware – Cherub beat on along the coast to Well’s Bay. Ignoring the line of moorings Johnson proceeded towards the cliffs and then, when he was almost ashore, kicked his anchor over the bow.

“Why d’you pick that spot?” we asked him, over the VHF. “We wanted to climb the ladder…”

“I picked this spot because it’s sheltered!” Johnson replied, with a chuckle. “I’m not going to anchor out there in that sea; and I’m not going to use one of those moorings either. I don’t want to spend the night pitching up and down. Over here, close under the cliffs, you can get out of the wind. You’ll find that the sea, in this little corner, is almost flat.”

And so it proved to be.

Gotta Get Up to Get Down

The following morning the wind was down a bit, and our little nook in the corner of Well’s Bay was almost calm, but landing was still out of the question. The swells still rolled into the bay, and although they hardly affected our yachts – anchored, as they were, in around eight metres – when they reached the rocky shore the waves tripped over their feet and came tumbling down in a crash of foam.

“In the summer there’s a beach over there,” Johnson told us, “but in the winter it washes away.”

We looked longingly at the site formerly occupied by the beach and at the road which climbed from the shore and which, we were given to understand, led ultimately to the village at the top of the old volcano.

“The village is called Bottom, because it’s in the bottom of the crater.”

It would have been nice to be able to say that we had climbed up to the bottom… but the glimspe that I had already had of the island tended to suggest that the settlement would probably be “nice” rather than quaint, with tarmac roads and new cars, and with houses which would be less like the colourful wooden ones that used to lie dotted over every Caribbean island and more like the new ones being thrown up in Antigua. The few houses which peeped out over the sea would have been classed by a property broker as villas.

Why is it that poverty is almost always more picturesque than riches? Surely a person with appalling taste is just as capable of expressing himself in a humble abode as in a biggger one?

It’s Not Who You Know, It’s Who They Think You Know

If we couldn’t get ashore then the next best thing was to explore the world which lay all around us, under the water. Scarcely had Roxanne and I jumped over the side, with our masks and flippers, when a big dive boat appeared on the scene. It’s skipper promptly began hollering at us, in a most unpleasant way, in an American accent.

“You can’t anchor here. You’re damaging the coral.”

This was not true, as I was able to assure the man. I had just that minute checked our anchor and it was buried in the sand. Indeed we were not even swinging over a patch of coral; there was no coral – alive or dead – within half a cable (100yds/m) of the boat.

“I’m not having you anchoring on my reef!” the American shouted back.

“My reef”…! Hmmm. Up until this moment we had been all set to move – for, after all, if the rules said that there was to be No Anchoring in this particular patch, who were we to argue? Coral or no coral, we could hardly expect to be allowed to remain in a place where anchoring is forbidden. But when the man called it, “my reef” the game was up. We weren’t going to be bullied; we weren’t going to go away just because some other fellow reckoned the place belonged to him – particularly as he wasn’t even a local.

A second member of the crew – a woman this time – now began to swear at Johnson.

Nick watched the proceedings thoughtfully for a moment, and then he switched on the VHF. “I wonder,” he said to the skipper of the dive boat, “if you know who it is that you are swearing at? You may not recognise this gentleman, but he is actually Paul Johnson.”

A brief paused ensued, and then: “I wasn’t swearing at him,” the American answered, rather more meekly now. “I’m just saying that he can’t anchor on the coral.”

“Mr Johnson has been coming to Saba for almost fifty years now. I think that you can probably rely on him to know where there is coral and where there isn’t.”

“Well, just so long as he isn’t anchored on the coral… You can’t anchor on the coral, you know… etc etc.” By the time he had finished speaking the man was almost apologetic.

The key to the successful conclusion of this affair lies in the fact that Paul just happens to share the same surname as Saba’s principal family, and the same name as the current prime minister. The implication was obvious… and our unpleasant American friend was evidently not too keen to have his claim over the reef discussed at government level.

Underwater Naturalist

The remainder of the day was spent in mending the mainsail, painting the view, and swimming with a trio of turtles. Surprisingly agile despite the weight of their beautiful marbled shields, the little turtles flew past flocks of brilliant blue fish, twisting and turning with all the grace of seagulls and now and then ducking down to nuzzle the weed-covered rocks on the seabed. Their long front flippers flapped steadily; meanwhile the hind ones were neatly tucked together, so that they looked more like a notched tail than two stumpy limbs.

As long as we only swam along on the surface – kicking as hard as we could to keep pace with the turtles’ effortless meanderings – Yurtle and his pals paid us no mind, but whenever we sought to take a closer look at the exquisite white etching on their dark flippers, or whenever Roxanne, failing to resist temptation, tried to touch one of them, the little animals would swiftly flick themselves forward a couple of feet, so avoiding such intimacy.

This is one place where underwater nature study scores over the terrestial kind: ashore, the animals and birds tend to flee as soon as they see us approaching, but in the world below the waves nobody panics until you actually try to invade their own personal space. And even then, they don’t go hurrying off to the other side of the sea mount. (The exception to this rule is reef fish, which do sometimes go to ground – but usually only when the visitor has been chucking spears at them.)

On the following day another American arrived, in a small launch, and told us that we had to go to Fort Bay and clear in. By now we were beginning to form a fairly negative view of Saba’s inhabitants: are they all American, we wondered? And are they all officious?

We had not set foot ashore and so rather than clearing in we decided to clear out – right out, and right away.

Time’s winged chariot was at our backs. According to our itinerary we were supposed to have left Saba on the 31st of March – and it was now the 13th day of April.

“Well, that’s pretty good going,” said Nick, “considering it’s us! I never thought we’d manage to keep up with the schedule.”

“But we haven’t kept up with our schedule! We’ve lost almost two weeks out of our Cuba allowance…”

Drop by next week for Part VI of this article.

I just love your stories, can’t wait for the updates – thank you so much.