Can We Save Our Sealife – or is it too late?

Well, it’s that time of the year again – and we’re still little nearer than we were last Christmas to our Southern Ocean goal.

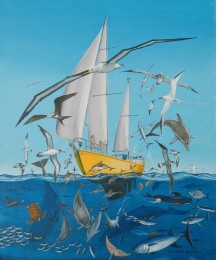

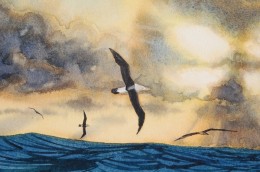

As you can no doubt imagine, we spend a lot of time dreaming of the journey ahead. The admiral’s latest painting brings this dream to life; it shows Mollymawk flying along amongst a flock of assorted seabirds, through a sea filled with fish and other animals. No, it isn’t really quite like this, out there on the ocean – we seldom find ourselves at the centre of a throng of birds; and certainly, one could never expect to see mollymawks and tropic birds on the same sea…! This picture is a intended as a synthesis of the life on the ocean wave.

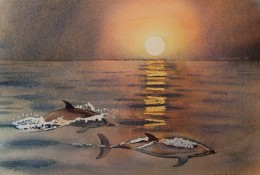

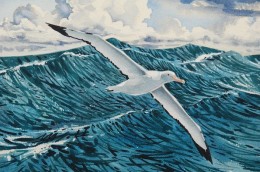

When we think of the passage south through the tropics and into the Southern Ocean, we think of the dolphins which will come to visit us and the whales which we will glimpse; we think of the shearwaters and the tropic birds; of the turtles; of the fish; of the mollymawks, or albatross… But then a little pang strikes our hearts: will the “mollies” still be there when we finally make it down to their end of the world?

Every five minutes, an albatross dies. And they aren’t dying of bird flu. They’re dying in our interests.

Every year 100,000 albatrosses, flying around in search of food, swoop down and snatch up what seems to them to be a tasty-looking squid. Unbeknowst to these birds, the squids hide a hook. They swallow their dinner – and the next thing they know, they are being dragged down through the water and drowned.

Quite apart from the barbarity, there just aren’t enough birds left in the world for us to carry on killing them at this rate. 18 of the 22 species of albatross flying around our oceans are threatened with extinction. They simply cannot breed fast enough to keep up with the rate of their destruction.

But, of course, the fishermen who set the deadly lures are not aiming to catch mollymawks. They are aiming to catch our dinner.

The albatrosses are not the only ones which are suffering:

“We have known for many years about the deaths of albatrosses and other seabirds in longline fisheries in the Southern Ocean, but I suspect that many people would be aghast to learn that a species rarer than the tiger is being threatened with extinction by fisheries operating in European waters.” This quote, from the RSPB, refers to the Balearic Shearwater, a close cousin of the Cory.

The Cory is common in the Canaries – but this may soon change, it seems, because it, too is a frequent victim of the long-liners. Then there’s the great shearwater “which suffers an exceptionally high annual bycatch rate of 50,000 birds annually in the longline hake fishery to the west of Ireland”.

Divers, grebes, and various kinds of duck are also being needlessly murdered as part of the fishing industry’s “bycatch” – but, as I have pointed out, we can’t really blame the fishermen; we must blame ourselves, and take steps accordingly. We cannot teach the birds the difference between a plastic squid and a real one and so we must encourage our leaders to take legal action to protect the birds. More importantly still, perhaps, we must change our own feeding habits.

“We have been waiting for a decade for the European Commission to take action to reduce the toll of seabirds in Europe’s fisheries. Further delays will result in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of birds. The technical adjustments to fishing practices needed to prevent this bycatch are often very simple but the political will to apply them has been lacking for far too long.”

For as long as the laws are lacking, the crime continues, and this means that when we eat those particular kinds of fish which are caught on a long-line, or by any other method which endangers wildlife, then we are taking part, by proxy, in the slaughter.

The birds are not the only ones which are suffering in our interests.

Each year, tens of thousands of dolphins and small whales are inadvertently slaughtered by fishermen.

Dolphins are smart enough to be able to tell the difference between a real live squid and a plastic lure – but they aren’t clever enough to keep away from shoals of tuna and other fish. Indeed, if they did keep away they would surely die of hunger; fish are their only food.

When a gigantic fishing boat encircles a shoal of tuna it often encircles a large number of dolphins at the same time. Ah, yes – we all thought that this problem had been addressed; we’ve all been buying tins labelled Dolphin Friendly Tuna – but recent reports suggest that the animals are still dying in those same purse seine nets.

To take the Mexican tuna fishery, for example:

“In an August 2002 report, U.S. government scientists admit that two dolphin populations in the eastern Pacific Ocean are seriously depleted and may not recover for 200 years, likely because of the deadly chasing and encircling practices employed by the Mexican tuna industry. … Dolphin populations are less than half of what they were in the 1950s, when tuna fisheries began using massive purse-seine nets to intentionally chase and encircle dolphins, which frequently swim with tuna in this region. An estimated six million dolphins have been killed. …”

The evidence from this government funded survey was expected to force the relevant department to deny this particular fishery the use of the coveted Dolphin Friendly label, but despite the report the government announced a “no significant adverse impact” finding.

“Evan’s announcement allowed the government to weaken the “Dolphin Safe” label … This decision not only threatens more dolphins, but also deceives American consumers who have trusted the “Dolphin Safe” label since 1990 when all major U.S. tuna companies adopted it.” (From a US Animal Rights website)

“According to the US Consumers Union, there is no guarantee that dolphins have not been harmed, despite the various labels. This is because there is no universal and independent verification of the dolphin-friendly claims” (From Wikipedia)

Even when the tuna is caught by dolphin-friendly methods the fishery is still very far from being environmentally friendly, because thousands of tons of other fish which are not wanted by the tuna-catchers are also being rounded up and destroyed. So, too are turtles and sharks. Ten percent of the fish captured by genuinely “dolphin-friendly” methods is unwanted bycatch.

“Fishing practices used by the global tuna industry are contributing to the sharp decline of populations of sea turtles, sharks, rays and other marine animals. Marketing campaigns attempt to make tuna fishing look like a quaint cottage industry, but the truth is that the tuna trade is all about big business.” (Greenpeace – For access to the full report, follow this link)

Dolphins and turtles also get caught in near invisible nylon nets and in trawl nets, drowning when they cannot free themselves and reach the surface to breathe.

As if this weren’t enough there is more bad news: the fish themselves are also threatened with extinction!

Put simply, many species of fish are being caught at such a rate that, like the dolphins and the birds, they are unable to breed fast enough. Certain species of tuna are on the endangered list, and so too are anchovies, cod, European hake, dogfish, conger eel, and a great many other fish which are often to be found in the supermarket freezers, or in tins, or on the wet-fish counter.

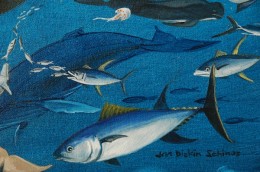

One of the most critically endangered fish is the bluefin tuna. It takes at least ten years to become sexually mature and so is very vulnerable to overfishing, but it is extremely valuable – a full-sized fish can fetch tens of thousands of dollars – and so it is highly sought after. Many countries, including Britain, have acquired a taste for sashimi – thin slivers of raw tuna – and in China the fish is becoming a gastronomic status symbol.

Farming these fish is not the way forward either. No one has yet worked out a way of rearing tuna from eggs, and so “farmed” tuna are simply wild-caught fish which have been fattened in a pen. Buying them doesn’t stop the depletion of the stock swimming in the ocean, and environmentalists are now calling for a total ban on the capture of this tuna.

No more fish doesn’t just mean no more cod and chips, or no more tuna salad. Down in southern Africa, where the fishermen have mopped up almost all of the sardines, the penguins are dying out. And up at the other end of the world, in the North Sea, puffins are starving for lack of their favourite staple. Whales, too, are said to be threatened by the size and scale of our South Atlantic squid fishing industry. Everything is beginning to feel the pinch, it seems. Even the fastest and fittest of Nature’s fishers cannot compete with a fleet of long-liners or a ship setting a huge purse seine net.

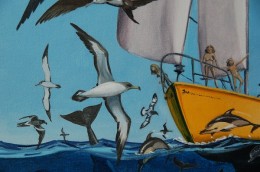

Roxanne’s collage depicts the scene all too clearly. With our advanced technology and our huge numbers, we are rounding up everything that swims in the ocean.

And then there’s bottom trawling, which just tears up the whole seabed and destroys and captures everything that’s down there.

By our greed, we are threatening the entire marine ecosystem.

Eventually, if we keep on the way we’re going, the sea will just be one big blue desert.

We have to do something about all of this. The UN is talking about doing something to control unsustainable fishing, but – hey, just look how effective their global warming policies have been, so far!

We have to do something, ourselves – and since the fishing industry heeds only the sound of money rattling into the bank, the only thing that you and I can do at the moment is to vote with our purses and our dinner plates. Until we can come up with a better solution we need to stop eating fish whose capture means the death of seabirds or dolphins or sharks and turtles, and we need to stop eating endangered species.

Dominating our painting of the world’s sealife is a black-browed albatross, or mollymawk – of course. There are two others in the scene, and there is also a wandering albatross. This bird is the biggest in the world, with a wingspan equal to the South American condor. Isn’t that something worth saving?

To the left of the scene and towards the foreground we find a Cory’s shearwater – the bird that makes such a wonderful noise at its nesting site – and to the right of the boat there is a great shearwater. As we have seen, both of these species are endangered by our modern fishing practices. The storm petrels flitting about over the water are too small to take a fishing lure, and so too the tropic birds – but the dereliction of their ocean home will harm them too, alas.

Under the water, in the clear blue sea, we find a small school of spotted dolphins and a couple of common dolphins. These species are threatened by the tuna industry.

The fish in the foreground is one of the very last bluefin tuna in the world. Isn’t it terrible to think that, because of our greed and our stupidity, this fish may soon be extinct?

In the distance we glimpse a sperm whale (lifting his flukes) and a humpback whale. Fortunately, as a result of the protests made by a few concerned individuals, these beasts are no longer hunted – except by a very few, mediaeval-minded nations. But the would-be whalers are constantly trying to overturn the ban on killing cetaceans – they say that numbers have now recovered! – and so we need to keep the pressure on.

In front of the sperm whale, we see a loggerhead turtle. All species of turtle are endangered, partly due to our fishing practices but also because many of their breeding sites have been developed for tourism or otherwise disrupted.

Turtles are also some of the principal victims of our mad habit of dumping non-renewable resources, such as plastic. Most of the rubbish floating in the oceans arrives there from the land, having blown offshore or been carried down rivers. So far as the turtles are concerned, the worst item of rubbish is the plastic bag. Seen from below, a plastic bag floating near the surface of the sea looks just like a jellyfish – and jellies are a young turtle’s staple food. When they swallow a plastic bag, they choke to death.

Plastic bags are finally becoming a thing of the past, and it seems that we will all need to cultivate the habit of carrying a thin cotton bag in our pocket (for those times when we weren’t planning to shop, and haven’t brought along a fleet of tough hessian bags…) In the meantime, while they are still in use, if you must dispose of a plastic bag please tie it in a tight knot. That way, it is less likely to blow around.

As it says on the dolphin research centre website : “Each day you have the opportunity to choose, and to change your behaviour. … Industry responds to the needs of consumers; namely you and me. No matter where you live, your personal choices affect the health of the oceans.”

If you would like to know which fish you can still eat with a relatively clear conscience, take a look at the lists published by the Marine Conservation Association. One shows which fish to avoid, and the other tells us which fish we can still eat.

The matter is still not entirely straightforward, because even when the tin of tuna is labelled with its exact species, we still don’t know where or how it was caught, or how many other animals were killed during its capture. In which case, perhaps we should err on the side of caution, and eat veggie burgers and nut roast…

Meanwhile, if you’re looking for a gift for a child, this Christmas, and you want to spend your money in a way which will benefit the environment, you might like to consider buying from the RSPB.

Amongst the RSPB’s many campaigns is one which seeks to protect the mollymawks.

Essentially, the aim is to educate fishermen in the methods by which they can try to avoid ensnaring birds – because, after all, fishermen don’t actually like killing birds either. Sending missionaries to preach to the heathen has always been a costly business, of course, and in order to pay the expenses of their Albatross Task Force the RSPB needs funding. Their fund raising merchandise includes a range of cuddly toy birds, and amongst this flock is a large fluffy albatross! Hey, I want one!

Roxanne, when she was small, had just one rag doll but she had dozens of cuddly animals – including badgers, seals, dolphins, an octopus, and a gull. Thus it would seem that this is an ideal present with which an environmentally-concerned adult can introduce the love of nature to a child.

Happy Christmas!

Tied to the problem of long line fishing is the fact that albatross are feeding their chicks plastic, mistaking bottle caps, lighters, and more for food. The chicks feel full but are starving.

Sea birds and marine mammals don’t have choices about what to eat, humans do. We can survive quite well without sea food in our diets. Considering the levels of mercury in top predator fish such as tuna, we woulld do ourselves a favor to stop eating them.

In Florida they have found female dolphins live longer than males. This is because the females offload some of their accumulated toxins in their milk when they birth their first calf. That calf almost always dies but the mother’s life is extended.

Everyone has the power of one. The most effective thing to do is to choose not to spend your money on sea food. If you want to eat a fish, catch it yourself.

Thanks for your comment.

We completely agree with what you say about eating only fish caught yourself, and we never buy supermarket fish. We do very occasionally buy fish caught by local fishermen, but generally we only eat fish if we catch it ourselves.